A Central Valley View from London Town

Documentary photographer Antonio Olmos sees London. He sees France... and Afghanistan and Russia and, most pointedly, California's small and rural towns

Antonio Olmos and I attended university in Fresno… is not a very West Coast sentence to say.

It’s legit though because on Monday Tony was in conversation with me from London and when our college years came up—with just a dusting of Mexican accent—he was incidentally equating scrappy California State University, Fresno with some boggy European place of higher learning—Cambridge, but with Super Sweet Corn. The imagery is whimsical enough for me to allow it.

One night in the fall of 1987, whilst Antonio and I attended university, the highly decorated photographer, the photographer Mark Mirko, another named Steve Pringle, and I saw Woody Allen’s September at Fresno’s Tower Theater. None of us knew from Uncle Vanya, the source material, but we knew the film moved us. When we walked out of the Tower doors and past the ticket booth, we sat on the curb and dissected the minor Woody, earnestly, for what in memory was hours.

That night epitomized my time in school not editing the campus daily. Our group of focused misfits bonded over art and books, punk rock, and coming from next-to-nothing. We hoarded journalism prizes as well. (As a show of discipline, our conversation skipped our short-lived punk band Anemic Tony and the Pygmy People). This week’s conversation, far from nostalgia, managed to feel like old times, primarily because of how Tony talks: The excited stammer when an idea gets him over his skis, high-pitched laughter… “shoes” unexpectedly becoming “chews,” but only after limey mode has taken full effect. It’s surprising and charming talk and maybe why—as Olmos discusses near the conversation’s close—people open themselves up to him on camera.

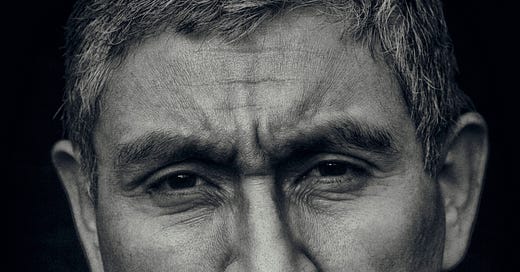

Photo by Antonio Olmos

About 10 years ago you were at the San Francisco Public Library. You had all of these pictures, and… you’d come all the way from London to show these pictures. People paid perfectly good money. And, they were these black-and-white pictures from your Daily Collegian days. What were you trying to do with that?

It was a group show and the other photographer was Matt Black. We were doing an exhibition about Mexican American, Chicano… the migrant communities, you know? These hidden stories in California that never get talked about.

When I was in university I used to hang around Chinatown. You know Chinatown in Fresno? It’s different now. Chinatown’s pretty much gone, but it used to be the Chinese community’s home. Then it became a community for a lot of the migrant Mexicans and itinerant Black farm workers. I just hung out there for four years while I was in university. That ended up being the show.

When you’re taking these pictures, you aren’t thinking that you’ll be showing them 30 years later, right?

To be honest, those pictures still have a lot of resonance. I’ve exhibited them 10 times in different places, including London.

Honest to God, I learned nothing at Fresno State.

I learned everything I needed to know for what I do from you guys.

Why do they hold up? Why are they still interesting?

If you know the value, if you know these towns that dot along Highway 99… if you go to the poor suburbs of all those towns you’ll see it’s really unchanged. The dominant language is Spanish and it’s made of up a new generation of people coming from Mexico and Central America, who inhabit the places and work in the fields…

I don’t think it’s changed that much. I go to Fresno once a year and I wander back into Chinatown, into Sanger, all of these towns around Fresno and there are parts of it that feels like a time warp. Not changed at all. Cars may be newer, people on mobile phones… but the economic situation is just the same.

I did a thing a couple of years ago on the lack of clean water in some of these towns, and that doesn’t just seem like you’re in a time warp—it feels like you’re not in California.

There are two Californias, one that’s the public face—the beaches, the beautiful landscapes, Hollywood and rich people, car culture and, you know, suburbia. But there’s this whole other culture that never gets talked about, or very rarely does.

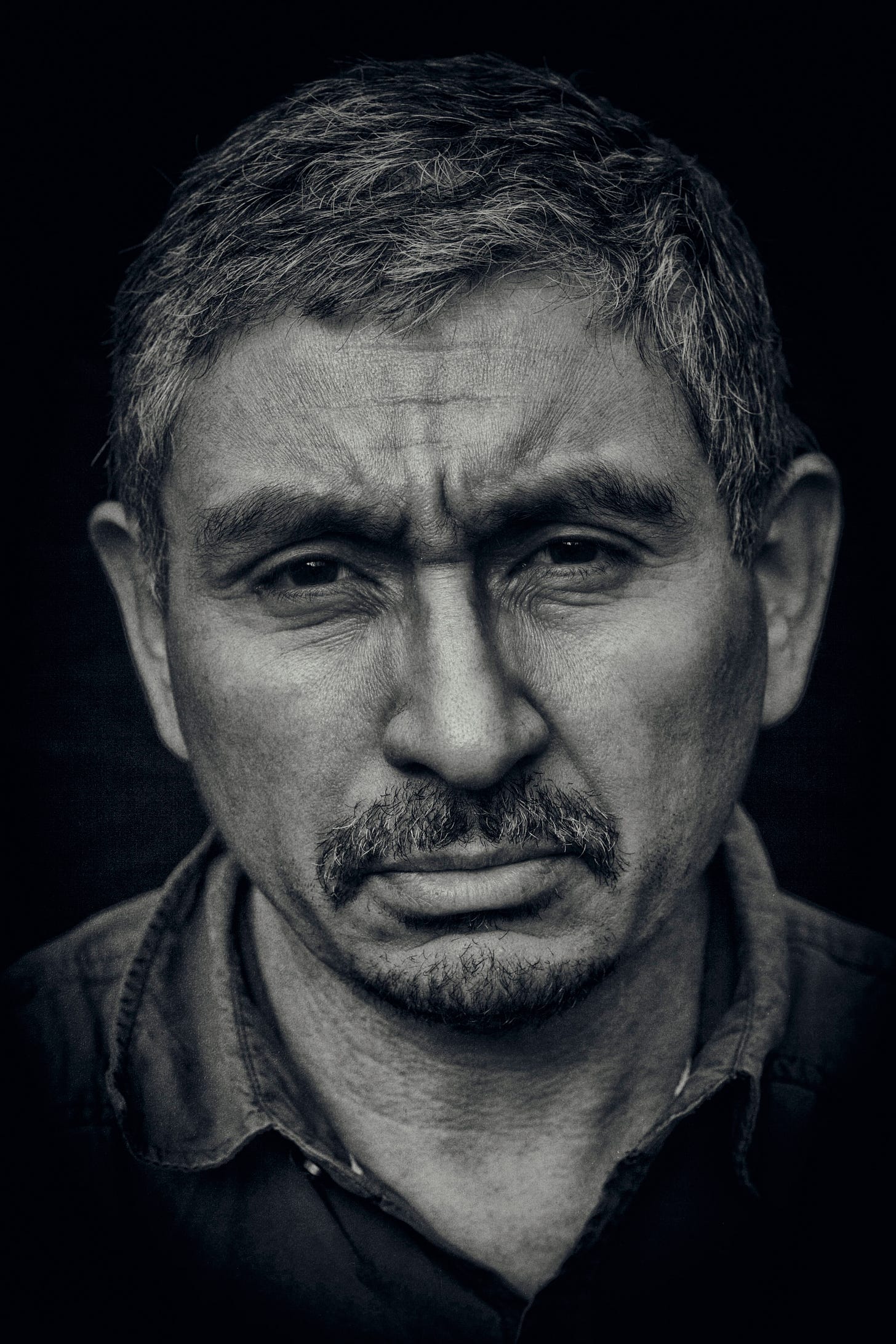

Photo by Antonio Olmos

I inhabited that culture for a bit, because we were migrants, ended up in Fresno and Sanger. The neighborhood is called La Chancla, which means The Sandal. The joke was that people on one side of Sanger were too poor to afford shoes. So they called it La Chancla, it was kinda true. Of course they could afford shoes, but they were poor, yo. You know?

That part of Sanger is still called La Chancla. It’s still where first-, second-generation Mexicans end up. Sanger is a really easy place to hide. Nobody goes to Sanger. Nobody goes to Reedley. No one goes to Del Rey. If you’re an undocumented worker, that’s where you hide out.

When you say La Chancla, I’m embarrassed to say that I only know it from throwing one at a child.

[Laughter]

How does someone get from Sanger-Fresno to London? You did some impactful work in Miami.

I think I’ve done impactful work everywhere I’ve been. I’ve just become a better photographer over the years.

A great over simplification of the story is that I had a huge curiosity to see the world. It stemmed from the fact that my uncle bought me a map when I was eight years old and he put it on my wall. A map of the world. I used to imagine what it was like in these places.

When I was a young teenager we ended up in The States. My mother was so busy working, she had no time to talk to me about books and literature and stuff. I don’t know where that [interest] came from; I grew up in a house with no books. Every book in the house was my book, that I bought. But I read them, got more curious about the world, kinda stumbled onto photography. Photography, I quickly realized, was a passport to get me out of where I was at.

You know, the traditional route for somebody who’s studious like me was go to university, get a professional job like a doctor or a lawyer… be a civil servant or something respectable where you wear a tie and requires a university degree. That kinda did appeal to me, but…

It’s kind of unconscious… I made a lot of decisions that could be considered fuck-ups when I was young. But that led me to the life I really did want, ya know? I live in a great city. I’ve seen the whole world, and all because I had a camera. [Laughs]

No one in London ever called me a Paki. I would go to Northern Ireland

and get called a Paki. Someone would come up to me and say, ‘Hey, don’t

come up here, Paki!’ And I would say, “Actually, I’m not from Pakistan.

I’m from Mexico.’ And they’d say, ‘What part of Pakistan is Mexico?’

One thing I’ve learned is that to be racist you have to be a real dumbfuck.

How did I get here? Once I figured out that I wanted to be a photographer I just worked my ass off. I had a good work ethic. I figured out what I needed to do. I did internships. First I worked at my university newspaper, then internships and a job. I knew that when I was working at the Miami Herald I wanted to be an agency photographer and travel around the world. Which I did. I knew that a photographer who was going to do what I wanted to do has got to live in Paris, London, or New York. So, I had to choose one of those places.

It wasn’t a straight line. These decisions were like accidents. I kinda did know for a long time, even when I was at the Daily Collegian in Fresno, that I was going to end up in New York, Paris or London. I knew it, you know? So when the opportunity rose up for me to be in one of these places I took it.

I just happen to be on Wishon, roughly Wishon and McKinley, just down the street from the apartment Pablo had when we were in college. The infamous argument about migrant workers rights. [Laughter] I have coffee with Pablo, right below his old apartment sometimes… you mentioned fucking up in college, and there was a lot of seriousness, juxtaposed with a real commitment to fucking up.

What was interesting to you about those times? You didn’t come into school to be a photo journalist, did you?

I kinda did. When I started Fresno State I enrolled in photo journalism. Before that I was bouncing around, trying to figure out what to do. I traveled a little bit in Mexico, a little bit in Latin America.

I could have gone to San Jose State, but I was so poor I couldn’t leave Fresno State to be a photographer. Being close to home allowed me to have cameras and buy stuff, be free to wander around with my camera. If I had gone to San Jose State, for example, to study photography I would have had to have a job to pay for my apartment. I would have had a lot of costs, and that would have diverted from being a photographer.

Honest to God, meeting you, and Kurt, and Lane, and Mark, and Thor, and Gary, and Akeemi.

Akeemi!

Yeah. The older I get, the more I realize how lucky I was to be around you guys. It’s really weird. I hate to call it intellectual. But in that bullshit kind of way, we were. We kinda hid it by joking around. But I remember arguments with you. You were passionate, I remember we were arguing about about Metal Machine Music [Laughter] by Lou Reed. I mean, really arguing about it, you know? We were serious about music and art and books and films and the things we did, writing and taking pictures. It’s a very Anglo-Saxon thing, that you don’t want to come off as pretentious, so you hide it by bullshitting and joking and drinking.

The author of this Substack is often at the center of news team group pics. In this John Walker photo, he’s got the arm of Antonio Olmos around him.

When I went to Mexico City and lived there for awhile I was shocked that everyone was kinda reciting poetry and talking about their favorite book—without embarrassment. They didn’t have to use joking and the stuff we did to hide the fact that we loved that stuff.

You’re calling it Anglo-Saxon. Isn’t it specifically an American thing, or do you see it in England, too?

You see it in Britain, too. I see it in Australia. I’ve seen it in New Zealand… You go to France, you go to Italy, Russia, anywhere in Central America—Latin America— Mexico, people… they’re pretentious, but they do get a great joy from learning and talking about stuff.

That’s why Monty Python is so brilliant. Through all of the bullshit and funniness and jokes, they’re pretty smart guys. I’m not saying we were Monte Python-esque. I’m saying that we were a group of individuals who were very smart, very dedicated, very hard-working. Very passionate.

Honest to God, I learned nothing at Fresno State. I learned everything I needed to know about what I do from you guys. The only class that blew me away was Philip Levine. Remember Philip Levine?

Of course.

He taught at Fresno State and I took his literature classes. He was fucking brilliant. Outside of him and a couple of other people, when I look back on my university days I think of you guys, completely.

I had an ongoing argument with T. James Madison, aka Frank Jones, in that he would say that it was an amazing remarkable time and I could never accept that something so amazing would be happening so early. And I’d be like, “This is bullshit. Our lives are going to be way better than this. I’m going to know more, smarter people. [Laughter] In the moment I couldn’t appreciate it.”

Let me be honest. I’ve met some amazing people. My friends in London are fucking amazing. But if I transplanted the people I just mentioned to London, got you a flat, got you a job, you guys would not be fish out of water. You would not be fish out of water. No way. You would be so comfortable here.

How long did it take for you to adjust? I know it was hard for you as a photo journalist, that they thought you were a “Paki,” but you don’t know the town. How do you do that?

First the Paki thing. No one in London ever called me a Paki. I would go to Northern Ireland and get called a Paki. Someone would come up to me and say, “Hey, don’t come up here, Paki!” And I would say, “Actually, I’m not from Pakistan. I’m from Mexico.” And they’d say, “What part of Pakistan is Mexico?” One thing I’ve learned is that to be racist you have to be a real dumbfuck.

I can honestly say that in London I’ve never experienced overt racism. I’m sure that somebody maybe didn’t give me a job because I’m not from London. But the whole world lives here. Nobody gives a fuck where you’re from. I can’t say that about Scotland or other parts of England, but in London I’ve never had doors closed to me. I’ve been to Hamburg, I’ve been to Paris. I’ve been to Milan to show my portfolio and a lot more doors were closed there.

But how do you adjust to doing journalism in a country and you don’t know it?

A lot of lucky breaks. I had a pretty good portfolio when I landed here, so people would see me.

I had a lot to figure out. Using one example: I love The Clash. I listened to The Clash, repeatedly, for 10 years before I came to London. I get to London and realize I didn’t understand half the songs because I didn’t live here. These little references they make. They’re not a world band, they’re a London band. Talking about London all of the time. Obviously, the music is universal, but when you live here, the references: Oh! This is the place. This is Hammersmith Odeon, this is the Westway.

I had a huge learning curve that wouldn’t have happened to me in, say, New York. We spoke the same language, but it’s a whole different culture that I had to learn quick. Luckily, I wasn’t a TV presenter. That would have been impossible for me. I was a photographer and my ignorance of the culture didn’t really get in the way. In fact, it probably helped me because everything was new to me. Everything was visually exciting to me. I could make pictures that someone who was local and grew up here never could.

I go back to Fresno and I have a hard time photographing in Fresno because it’s very familiar to me. It’s the same thing with London. It’s so familiar to me that I find it hard to take pictures.

Let’s talk about the war zones and tough places that you’ve shot. Are there ways that it’s enhanced your life? Or did it just damage you?

You know, I’m not of those people who can… [sighs] my mom, when she was young, growing up in Mexico, in Baja California, she used to see people die all of the time. Her father died in front of her. Neighbors would die in front of them. Everyone went to everybody’s funeral. She knew people who had polio. And she always ground it into me that, living in America, we were very privileged because I had never seen anything like that.

I had a sister who died when I was 33. Other than that, death was something foreign. So when I started going to war zones I had this thinking: I’m here because I want to be here. Any trauma that happens to me is self-inflicted, you know? It’s hard to say, Oh, I’m a damaged individual because you watched somebody’s house blown up. Or you saw someone bury their kids. You can’t in any way equate yourself with what they’ve gone through. So, if I couldn’t handle it then I wouldn’t go, but I think I can handle it. I’m not thinking about me. I’m thinking about them, you know?

I know people get post-traumatic stress and stuff, and maybe I’ve never seen anything so horrible that I was damaged for life. Thank God for that. I’ve seen people blown up. I was walking around Nablus with a photographer friend on a really boring day and suddenly we heard this swoosh and a car about 50 yards in front of us got blown up. Apparently there was a militant driving in the car and the Israelis blew it up. It was just massive metal and fire and burning bodies. It was quite shocking. To equate what I saw with what happened to that man and what his family is going through? I think it’s kind of ridiculous.

Maybe that’s just me. Maybe I haven’t seen too much… I’ve seen body parts, I’ve seen dead people. I’ve photographed dead people. I rarely publish the stuff because it doesn’t make an interesting enough photograph… if I was just doing more (of that work) I might get damaged, but I do other things. I just got finished photographing a bunch of punk rockers… I come out of these situations thinking about how lucky I am, not the other way around.

When that stuff happened in Nablus, the missile shooting, my first thought was, Wow, some car just got blown up! It takes me about 10 seconds to realize that I’m supposed to be taking pictures here. I’m famous for missing the moment. [Laughs] Because I’m still a human being. I’m still shocked and surprised and awed by these things that happen in front of me.

Is the stuff you did with the junkies in Afghanistan your top work, or do you have such a thing, a pantheon?

No. The junkies thing, it’s a well-trodden story. But basically the first Taliban got rid of the heroin trade. Then the Americans came and the heroin trade came back. A lot of people became rich off the heroin trade. Ninety percent of it is consumed by Americans and Europeans, but there’s so much produced that it makes a local junkie population.

Why would they sit down with you? Why would they go for that?

[Pause] You know? I am still amazed that people let me photograph them. I knock on people’s doors and say, “Hi. I’m from London!” I try to give this quick, personal story that I think disarms people: Hi, I live in London, but actually I’m from Mexico and blah, blah, blah. And I think I sound very unthreatening and friendly.

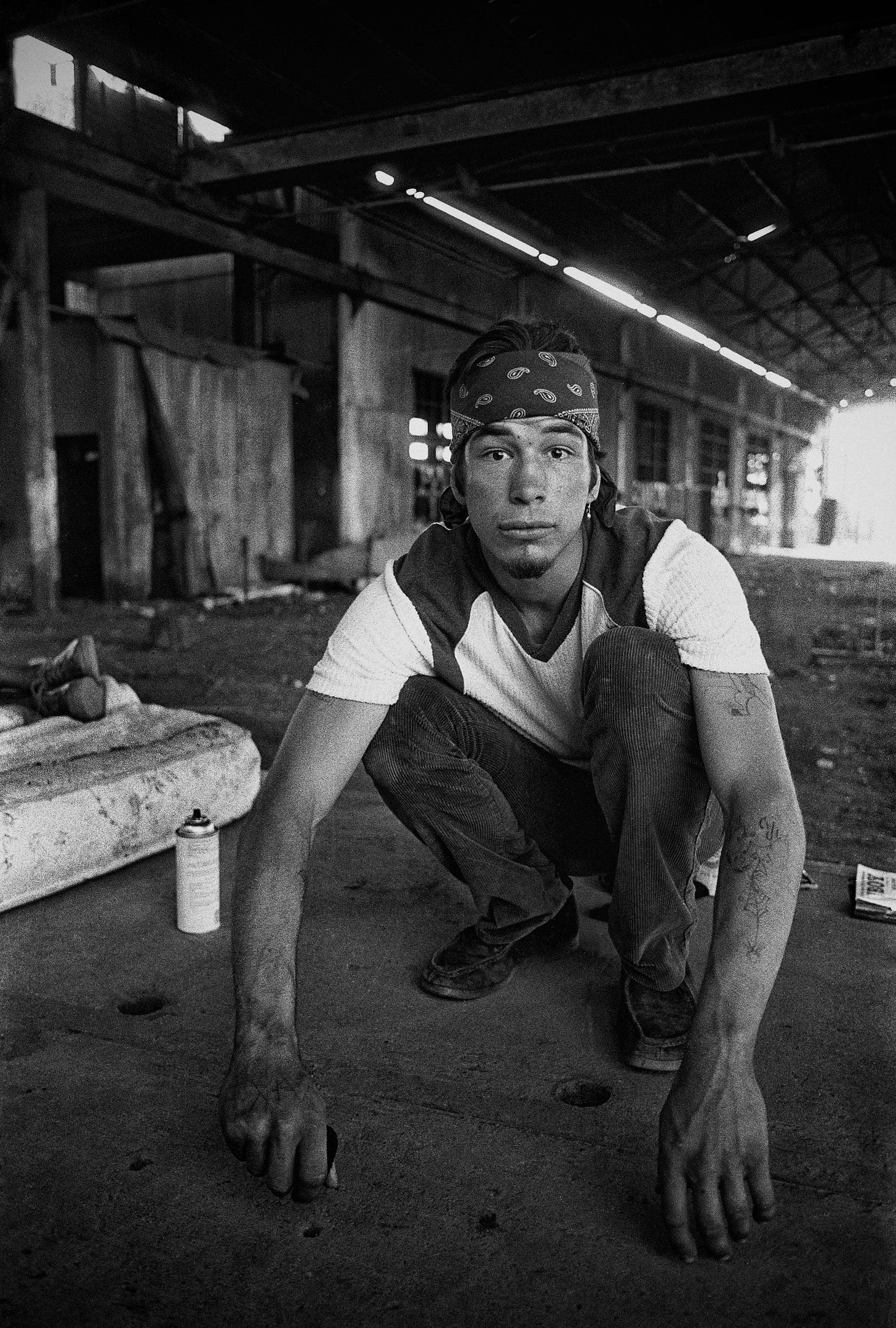

Photo by Antonio Olmos

[Laughter]

And people are like, Okay. Come on in! It’s crazy. That’s what I do for a living. I knock on doors and get into these environments where I have to make people trust me. I don’t have the luxury of hanging out with them for days on end.

Talk to me about the murder book, the doorways.

I’ve always wanted to do something on my doorstep in London, a big project. It kinda happened by accident. A woman was murdered by her boyfriend, a couple of blocks from me. And I found about it three days later. It was right in my own neighborhood, and it wasn’t in the news or anywhere. This woman got murdered by her boyfriend and it was completely silent.

I have to give the context that there’s very little crime in London compared to any big city in America. I was kind of amazed, so went to the house and made this really boring picture where the murder happened. Then I started paying attention and a few days later another woman got murdered, in another town, but—again—murdered by male members of their family.

It didn’t make the news. I would go to the places and kept trying to figure things out. Eventually the fifth or sixth murder in London was gang related. Some young Black kids got into a fight and they stabbed each other. One kid died, and that made the news. Oh my God. It was all over the BBC and the right-wing tabloids. The BBC didn’t sensationalize it, but they reported on it.

And that felt kind of weird. Four women had been murdered, no news. One Black stabs another Black kid and boy it’s big news. I thought, consciously, that it was playing to stereotypes because the first four murders were not Black people. They were white people. Domestic violence and stuff. And I quickly realized that there’s a narrative about murder that even Londoners believe: That gangs are running around London stabbing each other—because there are no guns here—that they’re all stabbing each other and in fact the biggest category of murder is domestic violence, women getting killed by their partners or boyfriends, husbands, male family members. And that never gets talked about.

The second category of murder is men—in Britain I’ll say white men—beating each other to death when they’re drunk. They get into a fight about something stupid. But those never make the news. But if a Black man or young Brown man in London kills somebody with a knife, that makes huge news. In two years there were only 20 gang-related murders. The rest of them were alcohol related or domestic violence.

It was a way of photographing parts of London that nobody ever photographs and talking about certain issues. It’s partly art project, part journalism—something that didn’t fit into the category of a little photo essay in a magazine. I wanted to make a book about it and an exhibition of it. I succeeded at both. I got it published in 26 countries around the world, exhibited four places in Europe. A shitload of newspapers around the world carried it. I had a huge success with it and it was the easiest project that I’ve ever done. I just walked out my door and did it.

Is it it like being a survivor to be doing photojournalism at this stage of your life? You couldn’t have known the profession would largely disappear when you started doing it?

When I first started, people were, like, bemoaning the death of Life magazine or this or that—

Journalists are good at bemoaning.

Photojournalists are fucking big moaners. Moan and moan and moan. If the business was great they’d be moaning about something else, I don’t know.

In fairness, journalism is shrinking as an industry. There’s just so much information out there. My kid doesn’t buy any physical products. My eighteen year old consumes everything through a phone or a computer. He looks at the Guardian online or the New York Times online, but it never occurs to him to buy a magazine, a physical one.

So, yeah, I’m surviving. I’m doing pretty well, to be honest with you. Compared to most people. Even here in London I’m doing quite well. I have a nickname, Tony Ten Jobs. [Laughs] I’m quite busy.

What does retirement look for you? Do you retire?

Photographers don’t retire.

Great conversation. It's a special thing when you can always pick up where you've left off.

Great story! I am so proud of my brother Antonio!