BH 20: The space where you brace for impending injury

Knowing that my kids’ hurt is coming dominated the weekend.

“Truth is like poetry. And most people fucking hate poetry.”

—The Big Short. By Michael Lewis & Adam McKay ( “Overheard in a DC bar” )

“I know you!" shouted the smudged-face skeleton.

The passing little blonde boy was pointing up at me, super-cute in his day-worn Halloween costume. He was seven or eight—too young to be among my regular playground cohort—but I had showed him how to properly throw an American football just the prior afternoon. Upon connecting to that new physical currency, this kid had started to glow.

His father probably doesn’t know how to throw a tight spiral, either.

“You playing football good!” he said. Toward the direction opposite of me, the second-grader followed his classmates

The boy is from Eastern Europe. This was Thursday. Last Halloween. Without looking back, I yelled an echo into the elementary school hallway: “I’ll teach you more later!”

That will turn out to be among the biggest recent lies I’ve told.

Thursday was the last day of school for the week and my last day as an after-school activities director at this northeastern LA-area elementary school, forever.

I was assigned 18 students, but functionally had 30-40, as my table of fifth-graders became the hangout bunch, and those entitled little visitors insisted on me learning their names. How popular was my activities sojourn? I don’t even count that skeleton kid from Eastern Europe as part of my crew.

Back in September, a sixth-grade girl cried in my supervisor’s office because she missed my library session. Eventually I started a guest-list policy, to help me sort out which kids would get into my hang.

In an upset, the most soul-lifting moments had indeed been the first functional games of catch, sometimes with newbies so small I worried the football would harm them.

The approach to running activities was based on teaching-adjacent gigs I’d done before: That Altadena group home where I worked with troubled teens, my Oregon Humanities Conversation Project events, the The Green Goblins’s South Pasadena Little League mistakes that taught me so much, and the 2010s Pacific Northwest College of Arts critical-theory program. (At PNCA I was official Stoned Uncle to that grad school collection, my main value being constant reminders that critical theory is pointless.)

For Parents Day last week, my elementary school students presented a thoughtful and impressive collection of monster drawings. They learned to distinguish between modern myths—like Frankenstein—and the older Dracula myth. They learned to play and deal Crazy 8s and Speed where every other child in the program was stuck on Uno.

On the playground, I showed a couple of budding hoops junkies some advanced basketball moves and quarterbacked enough pick-up football games to do my right elbow in forever. In an upset, the most soul-lifting moments had indeed been those first functional games of catch, sometimes with newbies so small I worried the football would harm them.

When showing the younglings basic technique, my qualms over the game went onto a shelf that was then deep-stored in a closet. What we were up to was good. An undersized immigrant who has a leg up in America’s most favorite sport has an advantage whose value is hard to calculate. Since Taylor got into the act, the same is more true of American girls than ever.

Sports fluency is currency. So many doors get unlocked when you have it. Sports fluency, the stakes of a game, none of that was part of other kids’ cohorts.

This the part where I brag a bit.

I was so funny. Like, little kid funny. A tough one to pull off.

In August, when the assignment began, there had been a deep skepticism in my ability to relate to children. It had been a while since my own were that young. So, I began to watch a bunch of “good” kids flicks and disliked almost all of them. (An exception being 2002’s Rabbit-Proof Fence, which everyone should see.)

What I had taken in at summer’s end felt so manipulative that I doubted my ability to relate. Instead, the youths and I had rhythm, patter, rapport, whatever you want to call it. When we played cards I would maintain a baseline of byplay, clever-ish language, and silly asides. I asked questions and they delighted in the engagement. The feeling was infectious. Crazy 8s and Speed to the left and to the right. Lower-grade children at our table, asking to borrow a deck of cards.

Children from nine to 12 were constantly asking for a piece of “Mr. Alexander.” Pretending I hated their neediness was part of my playground schtick, but I loved their focus more than I’ve loved anything in 2024.

Class gets out at 2:40. Students will come streaming out of the building and to the snack tables. Knowing that my kids’ hurt is coming has dominated the weekend. No matter how much weed I smoke, that painful angst has fluttered up my gut. I’ve found myself making a heartburn face, and then reaching for the Advil; the base of my brain hurt.

The closer it gets to 2:40 pm, the more I expect to feel like dookie.

This fall has been like Dead Poets Society, only with girls, three-pointers and fifth grade 2024 humor. (Skibidi!) My over-the-top popularity was almost certainly a immigrant thing. The students at this school had seen an America full of Black celebrities and sports stars and aspirational commercials, but none of that culture was represented on campus until I came through

“We were promised Black people,” they might as well have complained.

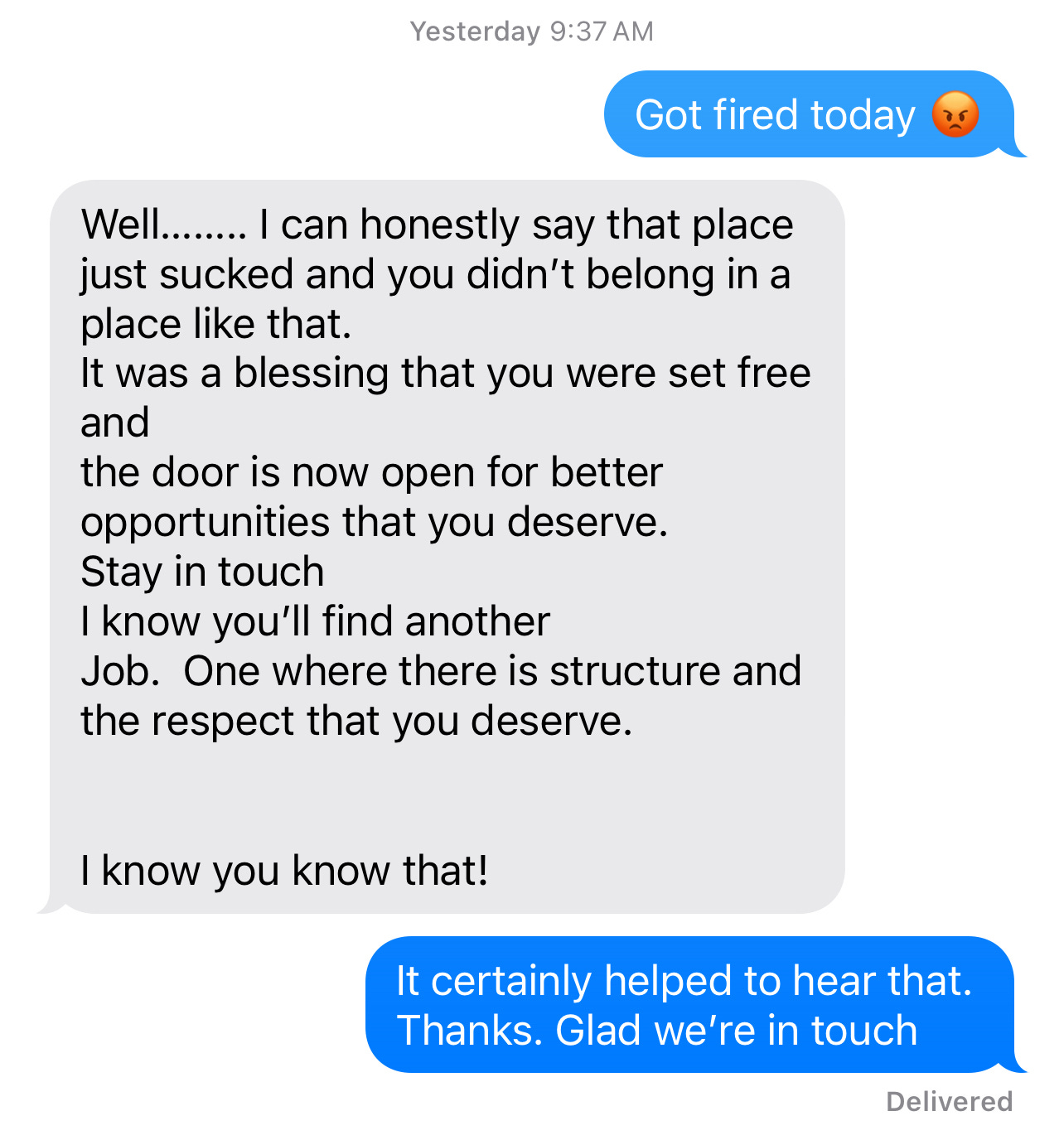

After I received the fateful Friday morning call, I texted a co-worker—a highly-educated woman in her 60s—who had been let go first.

I didn’t didn’t feel that way at all about the work environment. Yes, organization at the school was way short of awesome. I’d definitely seen worse, and the administrators were doing a better general job of caring for these rugrats than I ever could.

Being disliked by my peers was very different issue. From my first day on campus, few adults aside from the janitors would look me in the eye. Unlike rebel hero movie teachers, I did not thrive on the conflict. My natural response is to retreat into myself.

That never helps me, and this gig was no exception.

My Armenian peers in particular struggled to make eye contact. Now, in college I had interned in the Times’ former Glendale bureau and was hip to the racial antipathy. Those people were different from the second-generation Armenians I was hanging out with at Fresno State. They seemed to have absorbed the racist local culture, without questioning it.

As a Black person, you know a certain watchful eye. Be forced to recognize enough the prejudiced and watchful eye becomes a tangible sensation. Young Chris Rock described it as the scrutinizer telephone-dialing nine and one and just wait for you to fuck up.

I had that feeling in Glendale. The same Armenian woman who was instrumental in my first disciplinary write-up was integral to the one that got me fired.

If they wanna getcha, they gon getcha.

If I wanted to get into the weeds of what happened, I’d say that a power vacuum —based on, yes, disorganization—allowed someone who didn’t want me in the picture to tear me from the frame. Who wants to go there though? I’m very much on some its-better-to-have-loved-and-lost shit.

The past 72 hours have involved a lot of blinking back tears while listening to Fugazi. No goodbyes got said, but I was prescient enough to teach Rui Hachimura’s “ripthrough” move to my favorite Grade Five boy and girl hoopers

“This move will change your life,” I told them, separately. A simple move can do that for you, sometimes.

What time is it, anyway?

Tip me at Venmo, if you have such a notion. Thanks.