Emily Kruger's Thorny Portland dilemma

A young goalie in uncharted territory makes an enormous locker room choice

“If they’re great at sports they’re out of their minds,” argues Neal Brennan in Crazy Good his new Netflix special. Brennan’s rationale is that competitive sport at highest level is riddled with clinically-insane behavior, from Tom Brady trying to quarterback as he approaches 50 to the trials adolescent gymnasts go through.

“That shit should be against the law,” Brennan says.

I had pondered Emily Kruger’s sanity when she told me about the stand she took in 2016. Now an assistant soccer coach at St. Mary’s College, Kruger was a goalie with the National Women’s Soccer League’s Portland Thorns when the Black Lives Matter movement first caught fire.

Kruger, who has a background in the peace movement, decided to approach her teammates in support of Colin Kaepernick’s NFL protest. The young reserve’s life wouldn’t be the same thereafter. It was sort of crazy.

“I’m just sitting there like, Oh my god. What. Did. I. Do? That’s how I felt, because that’s how I felt—Oh man, I have this idea. And I really misjudged how the white women in the room would react.”

Emily Kruger is not even a little bit mentally disordered, as you’ll understand with the help of her words below. I left our Sojourn Conversation thinking we’re crazy, for letting insidious patriotism tests slide.

These words from our March Zoom call have been lightly edited, for clarity. They were speaking from their Oakland kitchen. I was crashing at a friend’s place in Glassell Park. There were guitars and cats all over, on my end.

Donnell Alexander: We have a good friend—a new friend—a person with a great story, as our guest this week. Emily Kruger, assistant coach at St. Mary’s College. Women’s soccer coach Emily Kruger, former Portland Thorn. Welcome. You showed me some cats earlier. I was very excited about that.

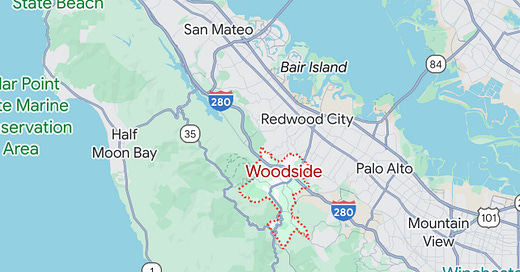

I wanted to go to your origin story. You’re a former professional athlete. You’re obviously teaching soccer at a school that has a strong program. I would like to know how you got started. You’re from The Peninsula, right?

Emily Kruger: I grew up in Redwood City, here in the Bay Area. California. I definitely was a natural athlete. As a very small child it was clear that I enjoyed running around.

DA: How so?

EK: I think my first memory—they’re tainted by photos—but I can picture my five-, six-year old photos: Me playing soccer, baseball, tennis, basketball. I was just drawn towards moving and playing with a ball, for sure. I was never interested in running or swimming. Things without a ball, to me, seemed boring. And still do.

DA: Okay. Was it always soccer?

EK: Soccer was one of them, but it wasn’t until I was a bit older, like the age of 12, that it really became only soccer as a really competitive endeavor. Even at that time I was playing tennis really competitively. That was my other sport at the time. Again, I played a lot of different sports. Tennis was an individual sport, and that was a struggle for me. My mom still rolls her eyes to this day about how I’d go to those tournaments and I wasn’t enjoying myself. I was always trying to talk to the opponent on the changeover. And they’d be like, ‘What are you doin’?’ I was meant for team sports, for sure.

Emily Kruger

DA: What was it about the individual sports that didn’t turn you on? Or, was it team sports turned you on more?

EK: Both. I’m a social person. Something I’ve always brought to my game was being a good leader, so when you’re out there on a court by yourself you don’t have that aspect.

DA: We’re getting a little bit ahead of ourselves, but when you were young, did you think of yourself as a political person when you were a developing athlete? Or were you just out there enjoying the sport and it was a getaway from everything?

EK: I was just enjoying it. I started to become… “politicized” isn’t the right word; that didn’t come along until later. Like, a little bit of an awakening, coming out of my own bubble with my privilege and with my blinders on—until, like, 15. I was pretty young, in high school, when I started looking around like: Wait a second, I think there are some things out there that are super unjust that I’m starting to hear about.

But, yes, it probably wasn’t until I was about 20, 21 that… I think [I got] the concept of becoming politicized, really having a political education. A people’s political education, right? And not like [pinches voice] “I learned in my classroom from a textbook.” I finally got to a point where I said, Wait a second. What’s up?

But it never felt connected to sports.

DA: Tell me about your experience as an athlete at Cal.

‘Kaepernick had started kneeling for the anthem and, obviously, made a lot of noise. In 2016 also, Black Lives Matter wasn’t mainstream the way it became in 2020, but it was huge in that moment.’

EK: Most of my teammates were focused solely on soccer, maybe a little on social. Not as much on school. The handful that were were players who weren’t playing the big minutes… That’s not totally fair. There were a handful of folks who were playing big minutes and cared about their studies. It’s just that I found myself pretty early on being a bit of an outcast on the team: I had other interests, I had other passions.

I can remember pretty early on talking to my coach. He was like, “I don’t feel like you care enough about the team’s success.” Which is code for winning. I said something like, “Yeah, we walk out this door every day and there are multiple people who are unhoused, standing right on the stoop of our stadium. I care more about why that’s a reality—how are we going to change that?—than I do about winning a dumb game.”

I already felt like that, and my studies were helping me process all the stuff in the world. And so, I really cared about my studies, I cared about my classes. I really liked my professors. I really liked the students I was around who were not athletes. To me, they were very interesting. I just found that in general. Again, I had some teammates who are incredibly intelligent, incredibly interesting.

In retrospect, I think maybe the way I used to see some of my teammates is not fair. I think I was being judgmental. But my world was just so much bigger than the team. And sports.

DA: I looked up your performance, and you were good. Is it easier for a goalie to be apart like that and still excellent?

EK: We’re definitely known for being weirdos in our own way. So, yeah, perhaps. I basically played every minute of my professional career, my freshman year to my senior year, by myself. My teammates generally respected me and saw me as… not necessarily an outcast, but just somebody who’s a little bit different. But I do think people easily in soccer say, “Yeah, it’s the goalie, of course they’re weird.”

DA: What year did you join the Thorns?

EK: It was 2015. February. That’s when you would report for the pre-season.

DA: Could you walk me through your getting signed? It’s not as though you were busting your ass to get into the league.

EK: No. I was quite apprehensive about continuing to play after my collegiate career. I really felt like the four years at Cal were quite enough. [It was] partly what we’re talking about. I just felt like there were more interesting things that I’m more passionate about that I wanted to pursue. I didn’t have any direction; I think already at that time I was like, I’m not interested in having a career at a non-profit. I was already thinking along the lines of, “Am I going to be an anarchist?” [Laughter] How am I actually going to be a revolutionary? I know that’s not in some job. I think because of that I had no clear direction.

I had a friend say, “Oh, we should go play in Europe, get an agent.” And I just sort of followed her. I said, “Yeah. Sure, sure. I’ll try it. Let’s see what happens.” Then the Portland Thorns called me. He offered me a tryout. He didn’t offer me a spot. I took the opportunity, because that’s the opportunity of a lifetime. I said yes, and then I got there and played well enough to get a spot for that first season.

DA: We skipped past something important. What did you major in at Cal?

EK: Peace studies.

DA: Were you seeing teammates in class?

EK: No. [Laughs] No other athletes in my peace studies major.

‘All I remember is being shocked it had taken me so long to have the realization that I was on a professional sports team that played games in front of twenty-thousand-plus fans and had games being broadcast on TV. I just hadn’t realized—somehow—that I was in a position of power?’

DA: You weren’t helping each other with homework?

We’ve played it coy long enough. There’s one interesting story—among your many interesting stories—that I’ve been hoping you’ll tell me. It happens around 2016. Can you take us there?

EK: I was in my second season, still young, but I wasn’t a rookie anymore. There was the election kind of looming and the Bernie Sanders campaign had picked up a ton of steam suddenly, and people who were Democrats were having to really look at ourselves and be like, Oh, am I going to vote for Hilary Clinton when we’ve got Bernie Sanders here. And then obviously the Trump campaign, he was starting to win all of the Republican primaries. And you were going, “Oh my God.” You knew it was going to be bad, but not that bad.

Kaepernick had started kneeling for the anthem and, obviously, made a lot of noise. In 2016 also, Black Lives Matter wasn’t mainstream the way it became in 2020, but it was huge in that moment. Initially huge.

I had been a part of all the demonstrations in the streets for two years at that point. For Kaepernick to kneel, Meghan Rapinoe, the soccer player, was kneeling. The WNBA had come out. Some NBA players and other NFL players. You were slowly having more and more celebrities come out and say, Yeah, we have a problem with police brutality against Black Americans.

DA: When I look back at that time now, I think of it as the beginning of a lot of things. In the moment, you couldn’t say it was early. It was just: This is happening. You couldn’t have known how mainstream these ideas would become, down the road.

EK: There was so much history. Sure, Black Lives Matter was a new iteration of Black Americans saying, “This country’s fucked up, which we’ve been saying for hundreds of years.” Yeah, my studies and interactions with all sorts of people at Cal led me to understand that that history still affects people’s daily lives and that all of those structures are rooted where they’re rooted.

When the boy who was shot in—

DA: Trayvon Martin?

EK: Missouri… no…

DA: There are so many…

EK: Michael Brown was really the first, when Ferguson really popped—when the officer who shot Michael Brown wasn’t immediately indicated like that—I was so ready to be like, “Yeah, this is fucked up.” Not like, this is fucked up; we should keep moving on. This is the thing we should be talking about. This is the thing we should be paying attention to.

That would have been, like, late 2014, right? So, yeah, by 2016 it felt like there was still momentum around that movement and those marches and those conversations were still on the top of people’s minds… in my world.

DA: So you decided to do something. You approached some teammates.

Really into what I’m doing? Contribute to the WCS travel budget.

EK: Actually, looking back, I’m kind of blown away by how long it took me to have the idea. I don’t know what month that Kaepernick started kneeling, but all I remember is being shocked it had taken me so long to have the realization that I was on a professional sports team that played games in front of twenty-thousand-plus fans and had games being broadcast on TV. I just hadn’t realized—somehow—that I was in a position of power?

Until one day it hit me. I think I was driving, and I went, “Oh, God. I am on a team with a platform, just like those athletes that I’m looking up to and saying, ‘Wow, how cool they’re doing that.’ I have that influence. I can ask the people on my team to join this.

‘The propaganda is, like, normal. We take it for granted.’

My initial ask was to two women of color who were on the team, who I knew would be onboard. And there were three Black women on the team, out of 28, maybe 30 people. So, five women of color. Three of them are Black. I reached out to them. We sat down in person—these are my friends, right? Comfortable, easy conversation. I said, “What do you guys think?” And they were like, “Oh yeah. Wow. Interesting.” Some of ’em are like, Yeah, we kinda thought it, too. But we didn’t want to go there.

We ended up agreeing that we should ask.

DA: You should ask who? You should ask what?

EK: We should ask the whole if they will do something to stand in solidarity with Colin Kaepernick as we say, Black Lives Matter. That was the basic ask. The details? We were pretty clear that asking to kneel during the anthem before a game was out of the question. We were not naive, thinking that they would say yes to that. So, we saw the WNBA players linking arms, putting their heads down. Kind of looking solemn during the anthem. We thought, that’s a good idea.

We said, Oh, let’s pitch it to the team and see what we can come up with—people will at least be interested. That’s what we thought.

DA: Right?

EK: That’s what we thought!

DA: I get the feeling it didn’t work out that way.

EK: We agreed that I should be the one to bring it up and instigate it to the team in the locker room. Again, you’re talking about, let’s call it 30 women in a room, after training. We had a group messaging platform that we were using and I said, “Hey you guys, I’ve got something I want to ask everybody.”

I sat with the five women. And the plan was: I’m going to pitch it, short. Thirty seconds. Pitch it and then I’m going to pass the mic to the women of color so that they can explain why they think it’s important. So, I start talking and 15 seconds into my 30-second pitch—which I’ve basically memorized—I get cut off, right?

Instantly, a couple of women are mad; both of these women are white, they’ve been in and out of the women’s national team and been around Meghan Rapinoe. They’re triggered. I didn’t realize they’d had all of these conversations with the national team about this protest action, and they were instantly really emotional. That’s where it didn’t go well and we were really surprised.

Then it turned into a really heated… argument. It was hard. It was really hard to witness. These people were like, “We don’t want to bring this into sports.” [A black teammate] stood up and said, “This is my life. I’ve had bad interactions with the police, my family has had bad interactions with the police. I don’t walk into this stadium to practice and play the games and leave my blackness at the door. That’s what I experience.”

And they were like, “Oh yeah. We hear that.” But it’s not going well. She’s getting visible upset, people are hurt, right?

And I’m just sitting there like, Oh my god. What. Did. I. Do? Because that’s how I felt—Oh man, I have this idea. And I really misjudged how the white women in the room would react. [Laughs] I really misjudged not bringing in the captains, just some things that in retrospect that I was like, not thinkin’ that through.

DA: The first thing I thought when you told me this story is that yours can’t be the only locker room this has happened in. In high schools, men’s and women’s and girls and boys’ sports, all the way up to the pros, these conversations had to be happening. Have you thought about that?

EK: And they play the anthem at every sporting event, which is ridiculous. Why is the national anthem playing at a high school soccer game? [Laughs]

‘Me and those two players, we do it every game. We play these teams, and it’s really interesting: Who’s kneeling, who’s not kneeling. Which schools do they play for? What do they look like? I’ve got this whole thing where it’s interesting to see who’s still engaging."‘

DA: I don’t know if I told you, but I was raised a Jehovah’s Witness. I never saluted the flag. Just having that point of view showed me the level of propaganda that we just take for granted. That’s how you get to “my country right or wrong,” How they think it’s a Christian nation.

EK: The propaganda is, like, normal. We take it for granted. Yeah, surely that conversation was happening everywhere. Currently, on the team I coach there are two players who kneel for the anthem. In my first big game of coaching college two years ago, in 2022, we were standing before the game and all of the sudden they were like, “And now for the playing—” I forgot that was a thing. I’m standing there. “Oh my god, they’re playing the national anthem. And literally, Donnell—I shit you not—two of my players are kneeling, and I was like, Hell, yeah. And I got down. It’s amazing how you need a little of that solidarity, right?

But as soon as I saw it, I just dropped. I was just like, Yup, I’m gonna do it. Here I am, I’m on a team again and we’re going to do this every game. Me and those two players, we do it every game. We play these teams, and it’s really interesting: Who’s kneeling, who’s not kneeling. Which schools do they play for? What do they look like? I’ve got this whole thing where it’s interesting to see who’s still engaging. Who’s taking that moment to say, Yeah, I’m going to kneel during the anthem… because I’m thinking of something else right now.

DA: I was talking about you earlier and this today and we were talking about sports writers like Dave Zirin and how there’s a new podcast that I listen to called The End of Sports. It got me thinking about the changing nature of the people who are playing sports. Young people’s politics are changing. Young people don’t love capitalism like they used to. How that’s going to impact the games down the road is really interesting to me.

But you and your teammates all made up and lived happily ever after. That’s how your story ends, right?

EK: Part 2. Horrible experience, right? Just really awkward and awful for everyone: They’re your teammate, you thought you were their friends, you thought you supported each other. Then, all of a sudden, this… moment has happened. It’s maybe 15 minutes, max, that interaction that we all had together in that locker room. But… oof, it shifted everything. Players are leaving mad. Lots of people are mad. Obviously the Black women are hurt and mad. But you’ve got the women that didn’t want to do it. They’re mad. The captains are mad. The coaching staff is mad. They told the GM and the owner—they were mad.

It was a whole thing. I got a talking to. “Why would you do that? We’re about to have our playoff game, and now we’re dealing with this!” I’m sure there were lots of conversations that I have no idea what they were, between teammates and coaches and the captains. Basically, what happened was that one of the captains felt more aligned with me and the five others who were asking for this. There wasn’t no one who was supportive, but there was a lot of silence. There was like loud “We don’t want this”, there was us saying, “we want this.” Then there was a lot of silence.

But what was cool is that within 24 hours, one of the captains came out to the whole team and said, I do think this is a good thing that they brought up. And it was someone with power and clout, this player. She told the team, We should think about something to do. We should do something. And she tried to get other ideas, so we had this other talk maybe two days later in the locker room. She tried to facilitate us, talking about what we could do—Is it a post on social media? Do we all post it?

So, she was kinda trying. And some people were trying. But, you know what happened? In the end of that meeting, the agreement was that we couldn’t do anything because we couldn’t come to a consensus. That was the goal, that the whole team would be on board, and it wasn’t possible. There were voices in that locker room that were just like, I won’t do it. I won’t say Black Lives Matter. I won’t put up a post, won’t be in a photo. I won’t do something after the game, I won’t do something before the game. Not the next day. They just said “no.” A handful of people. So nothing happened.

DA: A related anecdote. Maybe it’s related. There’s a documentary on Netflix called The Greatest Night in Pop, about the making of “We Are the World.” And Waylon Jennings shows up to do it, but then Stevie Wonder comes up with this idea of singing a verse in Swahili. And he says, ‘That’s it—no good ol’ boy never sang in Swahili! [Laughs] And he walks out. I imagine the sentiment in that locker room was a little more 21st-century than that. But people have their thresholds.

How did it impact you? Not just in that moment. You also saw the reaction in 2020.

EK: So we go into the playoff game, and we lose. The coaching staff puts that whole experience we had as not the reason, but a top reason why we lost the game. And I had this horrible interaction with the coaches after the season where it became abundantly clear that this was not where I was going to be working any longer and that this was not the right fit. So, I left. I said, “I’m not going to do this.” I found another opportunity to do something soccer-related, but with a little bit of a social impact lens, so I appreciated it.

Yeah, I got out of it, got far away from it. Had a really nice interaction with that captain. I’m a say her name. It’s Tobin Heath. She’s famous, she’s made a long career for herself. She and I sat at an end-of-the-year lunch, and she thanked me. She said, That was really cool, that you came to us. She said, I think it really showed me how deep this whiteness—not being able to say “Black lives matter” because they don’t care is just like, whoa! She was like, Whoa, we have some work to do!

So that was cool. I left her a little resource list, and said, Good luck with the group. And for my friends on the team who are Black, I just remember them being like, This is why our experience with white supremacy is real. We’re experiencing it, we’ve just got to go back to trying to survive. That’s essentially how they left it, because they stayed and kept playing.

Slowly I think the league was seeing a turn in more of them being activists, more so around LGBTQ visibility. That’s the main thing, even the players starting to unionize and talking about equal pay for women in sports. So, there was some activism-justice stuff starting to go on in the league that I was watching from afar. I was like, “Okay, cool. Good for them… but I know the truth.” [Laughs] At the core of it, I’m skeptical. Just knowing that there’s a handful of women in there fighting, what they’re up against. It’s a big fight.

And then, 2020. [Laughs] George Floyd’s murdered, and everyone’s at home during the pandemic. And there’s this celebrity movement of saying, Oh, I better say Black Lives Matter or I’m going to get canceled. So, I turn on an NWSL game and both teams are wearing t-shirts that say, “Black Lives Matter.” And both teams are all kneeling during the anthem? I was like, What? Am I in an alternate reality? [Laughs]

And then you have a couple of players—who are white—come out to the media and make statements: I didn’t feel comfortable kneeling, but I felt like I had to. [Laughs] What is happening? You felt like you had to? What? Really fascinating.

And then you had the league do this branding. That same coaching staff had BLM on just random pieces of clothing. Like, a hat, a sock, and an armband—they branded the whole thing! Just wild to me—and totally not surprising at the same time. I’m not naive, I understand what’s happening. And yet, because I’d been there and had that experience in 2016 I was livid. I was livid.

DA: Imagine there’s another Emily Kruger. What would you tell a young someone like them?

EK: You have a desire for justice, but you’re working in a space that’s capitalist, like most industries in the US. But it’s also celebrity, which is really interesting.

DA: So do you just have to swallow it? Is that space incongruous? Incompatible?

EK: Yeah, it’s a good question. It’s each person’s own journey. I left partly because of that. I think about one of those Black women, the one who said, This is my own experience. She was passionate, she was angry, and she was hurt. She’s still playing. She’s still in the league. I’ve talked to her over the past few years and she’s like, Ya know, I pick my battles and am not mad at the whole thing. I get to do what I love.

You reckon with what you reckon. That’s anybody. We’re all trying to make money in this country. You’re looking around at the place you work and the boss and the owner and you’re like, “Does this align, really, with what I care about and the legacy I want to leave?” I think, for most people to make enough money to really survive out here, usually the answer is no. It’s hard to find something that aligns, that’s what I would tell somebody.

What an impressive person.

Is she old enough to run for President yet? Terrible shame if not.