Johnny Angel Wendell—Double Local Legend

His song won Best Indie Single at the 1987 Boston Music Awards. In this century, the artist formerly known as Johnny Angel left his mark on LA talk radio. He and I go back

The Johnny Angel I knew didn’t have a Wendell on the end. Let’s get that clear straight away.

The Boston-bred rock star-writer-turned-talk show host will always be to me the burly street scribe who, in full punk regalia, marched me up Sunset to the Zankou Chicken on Normandie. This was late 1994, and I was just days into my move from the Castro District in San Francisco to the western edge of Hollywood. I’d found Johnny Angel bopping around my brand new LA Weekly desk—back then, music people bled into the editorial mix.

(For a minute, Carlos Niño was my intern.)

Johnny’s insistence that I be eating that chicken, pronto, bordered on religious fervor and, quite frankly, freaked me out a little bit.

But he was so right. To call that initial bite of Zankou Chicken in the garlic sauce amazing is to insult the poultry dish, to call the chicken’s mother a crack whore. The vast majority of first sexual experiences are less satisfying than first experiences with Zankou Chicken.

I digress, but not really. Johnny is one of my deepest street-level homies, reporter category. A knower of things. When we first connected we were in San Francisco—then a two alternative newspaper town— and he had dug up this lost rock god, a sixties force nearly disappeared into history. Next thing I know, the punk dude’s doing a fuckin crazy column about crime in LA. It was kind of a how-to column, in which Johnny Angel teamed with actual criminals to tear past the bullshit of traditional crime reporting. It’s the How To episode you won’t see John Wilson doing.

I’m unashamed. I don’t mind being seen and heard.

To me, shyness… life is way too short to be shy about anything.

Columns like that crime joint are why alt weeklies mattered. That more of their great American journalism isn’t available online is indefensible.

My man though has been more than a hard-hitting journalist and a leader of the first-wave punk band The Thrills. You’ve likely caught him in TV commercials or some streaming bit, playing a rough guy for a hot minute. Mostly, fans of LA talk radio recognize Johnny’s voice from gigs on KFI, KEIB, KTLK, Mike Malloy, and Alan Colmes.

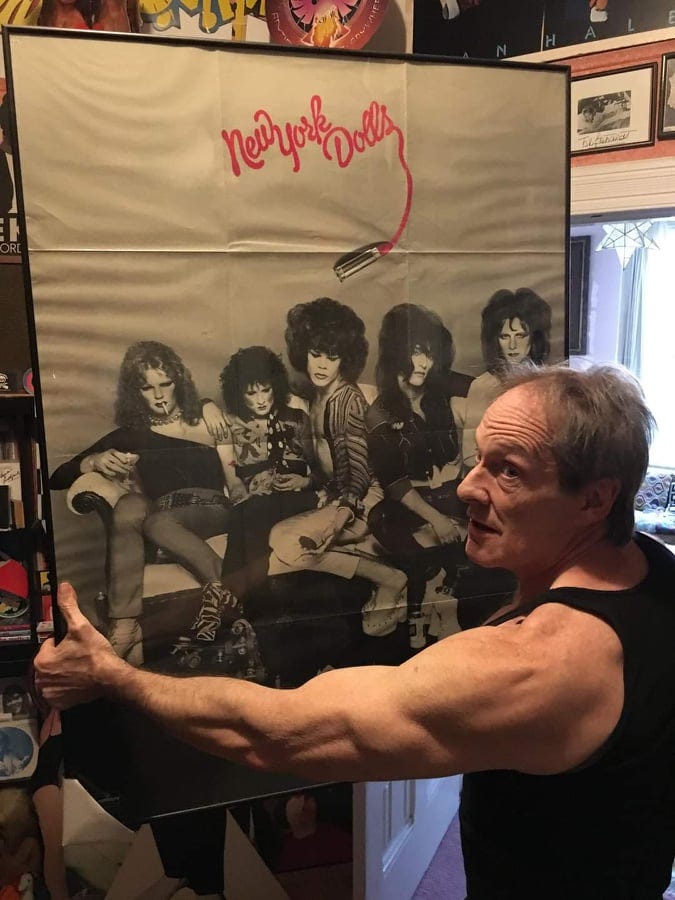

We did a Zoom sesh a couple of days ago. He and I were trying to remember when we were last in the same room, and I am now thinking that it might have been at my wedding. Golden Gate Park’s Conservatory of Flowers, 1995. Dude wore what memory says was an auto mechanic’s shirt. This week he was before me in what in more unenlightened times was called a wife beater. And Johnny looks pretty good in it.

At 67, Johnny Angel Wendell’s lost a bit of his punk rock snarl. He’s an involved, older dad, and one is not afforded cynicism in that game.

Note: When you see [laughter]? That’s mostly me laughing, not Johnny. Mr. Wendell knows how to hold for applause and laughter.

I haven’t seen you seen you in a long, long time.

The last time you and I were in the same room was a long, long time ago. We’re talking over 20 years.

I’ve always thought of you as one of the great talkers, one of the greatest talkers I’ve known on a personal level. I’ve known Larry Elder and I rank you in front of him—

Thanks. What a high bar.

I’ve been hanging around my girlfriend’s father a bunch and thinking a lot about nature versus nurture and I wonder, Where did you get your motormouth from?

Probably my own father. My father had an opinion on everything. The thing is, he didn’t have a governing mechanism that would ever get him to shut up. He would keep going long after he was wrong. I make my point and move on to another point.

Because I was a talk radio host for 20 years, it does re-route your thinking. You become much more linear in how you make a point. A leads into B, B leads into C, C leads into D. Everything is moving toward a conclusion of some kind, as opposed to just expounding on anything and everything under the sun.

When I first met you, we were both working at a newspaper called the San Francisco Bay Guardian.

Yes we were.

And my editor—and your editor—was Tim Redmond. I would turn in a column to Tim and he’d say, it was really good until the third paragraph, then you veered into the Johnny Angel Ozone. [Laughter] That’s what he would call it. In other words, your flight of fancy would demolish what you were doing.

When I went on the radio I learned that you can’t do that unless the audience understands where B links into C and C links into D. So, my talking skills—my communication skills—have always been good, because I’m loquacious. I’m unashamed. I don’t mind being seen and heard. To me, shyness… life is way too short to be shy about anything.

I will buy that.

Shy I ain’t.

I want to talk about your fame. Someone called me a local treasure in LA, and I’ve been wrapping my mind around what it means to be a local treasure in Los Angeles. And you kind of have it in a couple of places. I’m curious to know what it’s worth to be a local celebrity.

Not a damn thing.

Is it better than being a national one?

What’s the song? “I Second that Emotion”? When Smokey sings, [sings] “and a taste of honey’s worse than none at all”—that’s exactly what it is: A little bit of a taste is way worse than nothing. Then you have an idea of what it is you’re missing. That’s the gist of the song, the gist of that lyric.

Getting local notoriety in New England or in New York City or in San Francisco or Los Angeles just means you were present in places where lots of people like to congregate, and that can be on the pages of a newspaper. That can be a website. It can be a club where you’re playing live music.

Insomuch as my career or my life has been mostly in public, starting with being a punk rock musician in the seventies and then moving to California and becoming like a syndicated columnist and then moving into talk radio—I’ve acted in commercials. I’ve been in indie films and stuff—the most legit job I’ve had is what I do now. I’m a personal trainer now. It’s a one-on-one thing, it isn’t one-on-300. It isn’t a one-on-3,000. It isn’t one on 30,000. And it’s really been super gratifying. I really enjoy it.

Johnny Angel Wendell moving a New York Dolls poster at The Punk Rock Museum.

I don’t miss playing lots of gigs and I don’t miss writing for newspapers. I don’t have a Substack, I don’t have a blog. I don’t miss talk radio that much, because podcasts have sort have torn the audience away from that. And podcasts aren’t profitable, generally, so I never bothered with that. What did I do? Whatever was in front of me to do? I did it.

Let’s go back. Which band meant the most to you?

My first one, like everybody’s. It doesn’t matter what anybody says, unless you were in a group or were an individual performer that had enormous success the first time out, the band that you’re going to treasure the most is your first one. The first one where you played your own songs, the first one where they played you on the radio, the first one where you went from drawing nine people—of your friends—to 300 people and you only know a handful of them to 500 people and you know even less of them. It’s not like anything else. Being in a band is a peculiar endeavor because it doesn’t really have any parameters. It’s just you and people with you are cooperating on a shared vision—without any external molding, up until you get a record deal. And those barely exist anymore.

So, you’re just fighting your way through the dark with these people who are, in fact, your family. I didn’t choose my mom and dad. Neither did you. But you can choose your bandmates. Or your bandmates choose you. You don’t get to pick your audience, either. Your audience picks you.

Knowing all of those things in retrospect, as I do now, my first band is the one that meant the most to me. They’re the one I wrote my first book about. The one where I was no longer my father and mother’s son. I created a persona that I was more comfortable with and I did it of my own volition. I wasn’t Svengali’d into something. I wasn’t like a member of NSYNC or the Backstreet Boys where you have a Svengali who tells you what ya do.

That shows how old I am. Those bands ceased to exist about 25 years ago.

[Laughter]

Let me ask, because I know you will go on.

I will do that.

I’m curious because you have this East Coast-West Coast juxtaposition, does fame play out differently in a town like Boston than it does in a San Francisco or LA?

First and foremost, San Francisco and Boston are really similar.

Analogues even.

The number of people in the Bay Area I think is relatively close to the number of people in Eastern Massachusetts, Southern New Hampshire and Northern Rhode Island. The Bay Area’s a little bigger, geographically. There’s a tremendous amount of resentment in Boston aimed at New York. There’s a tremendous amount of resentment in San Francisco toward Los Angeles. So they’re very similar. I found that being a popular musician and sort of a man about town was tremendous, a wonderful feeling—for a while. But then it starts to feel really bad as you become keenly aware of the limitations of your reach.

I remember we won this [reaches for a trophy] my Boston Music Award. Best Independent Single: “Walk Like an Erection,” 1987. We were backstage, myself and some of my band mates and my old friend Robin Lane, who had a deal with Warner Brothers in the seventies and eighties. I was talking to Robin. She’d won an award and she goes, “How many people do you think know about this?” And I said, outside of the beltway road around Boston—Route 128, famous in Road Runner by Jonathan Richman—I said: Nobody. I laughed and said, “And I’m being charitable, Robin.”

You realized that it’s not a big deal. Some friends of mine were just inducted into some Boston Music Hall of Fame. I guess there is such a thing, but I don’t know how I’d react if they did that to me. I’ve kept a really low profile, as per my past, for the past 15 years. I’ve only been in Boston once in the past 15 years. I don’t really like visiting very much.

You know what it is, it’s like someone that you love and you’re having sex with someone and it’s wonderful and then you don’t love them anymore and you’re still having sex. The sex isn’t very good at that point. You’re kind of going through the motions. That’s what it felt like.

I interned at the Boston Globe and lived in Milton.

My second band used to rehearse there.

My point was that I used to know 128. It’s been a long time. And I do get you when you make that comparison to San Francisco. Can we go to San Francisco for a minute?

Do we have to?

I have this memory of you writing a long profile of a guy. Was his name Skip Spence by any chance?

Yes, that’s correct.

Yes!

Skip’s existence indirectly led to me moving to San Francisco. I was on the phone one morning. I was living in Los Feliz and talking to a publicity man at Warner Brothers Records named Bill Bentley. And both of us had recently received a box set from the San Francisco psychedelic band Moby Grape. We were both huge Moby Grape fans and Bill mused aloud, “Johnny, what do you think ever happened to Skip Spence?” Skip was the titular leader of the band, right? I said, I have no idea and Bill said, “I guess nobody will ever find him then.” The gauntlet was thrown down.

It’s like, nobody tells me I’m not going to find somebody. I said, “I’ll find em for ya, you’ll see”. And I did! He was in a halfway house in San Jose. I went into a pitch meeting of sorts, at the LA Weekly. Once a week you pitched ideas, as to what kind of feature you’d want to write in the future. I laid Skip’s story out, how important he was—how he’d vanished at the height of his fame. He was like the American Syd Barrett. I said I want to go up and write about him. One of the people at LA Weekly, a woman named Judith Lewis said, “That’s not a feature.” She said, “That’s a cover story.” I didn’t envision it that way, but Judith did. She had better perspective than I did. What did I know? I didn’t know shit, right?

I think that I will be remembered by the people I was around, but the fact is that a talk radio host, a columnist, a commercial actor, a musician of moderate fame is part of the great wheel of distraction that gets people through the day.

I went up to San Jose. Skip’s in a halfway house. He’s bipolar and schizophrenic… drunk, and we had the best time. The two of us. I could keep his attention for hours. The people in the halfway house could not believe it. This guy would not connect two sentences together—how do you keep his attention. I said, You treat him like he’s a mindless indigent, like he’s a ding, and I treat him like what he was: rock royalty at one point. You treat somebody with respect, they’re happy okay.

The feature ran in the Weekly. Tim wanted a version of it for the Bay Guardian, so I rewrote it for Tim. And I had to rewrite it for the San Jose paper that Steve Buell ran. It ran in Relix magazine, it ran in a bunch of places. It was wonderful. It was a cash cow.

That was just when I met you. Exactly.

I had just moved to San Francisco. Was living in the Haight, and I saw you—

[Laughter]

—off-campus, away from the Bay Guardian one afternoon. You were walking down Haight Street, and… you just didn’t seem to be yourself. For some reason. And I said, “What’s going on?” And you kinda looked around furtively. And you go, like [leans forward] “I’m tripping on acid.”

And I looked at you with just absolute revulsion—I’m sorry, you don’t do that to someone on LSD—and I went, “Oh no, not you, too! This hippy nonsense! It’s not 1967! Stop! Why are you doing this! Times have changed!” [Laughter]

What’s so amazing about it is that you did do it while I was tripping, so that look of revulsion, it comes back exact. I think it was at Booksmith.

In front of Booksmith. It was on the sidewalk.

Daytime trip.

It was on a Saturday afternoon. It was just disbelief. It was like, “I thought this guy was okay. And he’s a hippy.”

If you had to make the distinction between the Guardian and the Weekly, how would you do that for someone who didn’t know?

The San Francisco Weekly was part of chain and the Bay Guardian was free standing. As I recall, the SF Weekly was owned by LA New Times owner. Lacey? That was his name. The Bay Guardian was the baby and the love child of one man, Bruce Bruggman, who was the publisher. Bruce had an issue. He had one issue that he was fanatical about, which informed everything at the Guardian. Bruce believed that people in the Bay are entitled to free electric power, and the fact that it was for profit and Pacific Gas & Electric had inserted themselves as the middleman between sources of power to the east—in the Sierras, I guess, drove Bruce crazy.

He couldn’t believe this happened. It shouldn’t be profitable. We’re the ones that paid for this infrastructure. Bruce was right. But he didn’t quite see it as microcosmic of what capitalism is, which is you always seek to insert yourself right in the middle, between the producer and consumer as the middle man, because that’s the most profitable place to be. If you’re the creator of the product, for example, you ‘ve got all kinds of expenses that the middle man doesn’t have.

Had he been more general, I think people would have been like, Oh I know what this guy is on about. Yeah, I agree with him.

But Bruce was super laissez faire about the entertainment section of the newspaper, which allowed me to have a column every week about anything I wanted to write about. You name it. And I would write about anything. It was just insane. I don’t even remember 95 percent of what I said in that paper. And I remind you that I was clean and sober the whole time, under 40 years old—so I had my faculties. But I can’t because it was just so freewheeling. Whatever I thought I wrote, and people really enjoyed it, because it was like the musings of a lunatic. A loquacious, literate lunatic. Pretty good alliteration, huh?

They let me do a gig that was half nightclub columnist and half political reporter, a job I’ve never seen since then. It’s also a job I never really stopped doing. So, all props to Bruce.

Also, what’s really interesting about the Bay Guardian is if you were a capable writer you weren’t constrained necessarily by your beat. I wrote restaurant reviews. I wrote movie reviews. I wrote about politics, I could write about anything. Anything. I could go to Tim or to Tommy Tompkins—the arts and entertainment editor—and I’d say, “What about this?” And they’d be like, “Yeah.” They figured, “he can pitch me, but he can deliver.” It’s like the old saying: Ideas are free property. Turning them into something is something else. You have a great idea? So what, if it doesn’t germinate, if it doesn’t become something.

The Guardian and the LA Weekly, especially. I was there before you were there. Then I moved to San Francisco and you moved to Los Angeles. Then I moved back to Los Angeles. I think that’s when your piece on your dad ran.

I wasn’t aware that you were going back and forth like that. I just thought you were in and out because… that was your gig. You had that great crime column, that you did with that guy?

Outlaw LA.

I used to joke that you were going to come out of that one a master criminal.

[Laughter]

It had the opposite effect. When you deal with these people—especially felons with drug issues can be really charming people, because they want something specific. So, they are not going to alienate you, because you have a wallet. Or you have access to fame. Or you have access to drugs. They are not going to fuck with you. They’re going to give you what you want because, inevitably, you’re going to give them what they want.

I loved writing that column. Eddie [Little] was one of my closest friends. We had a great time with that thing. The Weekly put up an advert inside the newspaper. It was Charlie Rappeleye and Howard Blume who thought of it: What if you… not write LA noir, because that subject is beaten to death; everybody sees themselves as Raymond Fuckin’ Chandler. Well, there was already a Raymond Chandler. Outlaw LA was specific people: how do they do what they do? And what do they do? And I found some lu-lu’s.

Name the top two or three.

My favorite one was Ronnie, Rest in peace. He died young, of an asthma attack, of all things. He was an… associate of people in prison gangs. And he would carry out certain tasks for them. He also ran an extortion ring which I believe he got busted for, at one point. He was very colorful and he and I got along swimmingly. How that is possible, I don’t know.

It’s like Skip Spence. It’s the same thing. You have to treat people, as a journalist, the way they are. You can’t go into it with this idea of, Well Skip has schizophrenia and Ronnie’s been in and out of the prison system his whole life—these people aren’t together like I am. To write about them like they’re an amusing subject? No! Strip someone of dignity and it ruins the story. Even a criminal has dignity.

What do you think you’re going to get remembered for? Never mind your children or anything like that, what do you think will stay on people’s minds the longest? Do you care?

No. I don’t give a damn. In order to last long in the public consciousness, you have to be enormously successful. I am not enormously successful. I think that I will be remembered by the people I was around, but the fact is that a talk radio host, a columnist, a commercial actor, a musician of moderate fame is part of the great wheel of distraction that gets people through the day.

It’s like, if I can come out, write a song and sing a song and play a song that can make someone smile in the middle of the day. I wrote this really silly love song recently. It took me about 10 minutes to write, and people just loved the song. It makes them happy. That’s great. But remembered for anything? Not after my peers are gone, not after I’m gone.

You can’t make a big production out of that. Human beings and the way they view their own mortality and their own importance is just… sad. It’s so that we’re less afraid of dying. Like, I’ll be remembered. That way I live forever even though, you know, my body is dead. No. If you ask somebody who was the most powerful member of the House of Whatever. Remember when Germany was millions of little tiny countries? Before they became Germany in the 1800s? “Who built this castle?” Nobody knows, nobody remembers, nobody cares.

Will they remember Bismarck and Metternich? They remember Gladwell and Disraeli. They remember Abraham Lincoln. They remember FDR, Martin Luther King. Those are people who are famous outside of their generation. Hate to say it, but Donald Trump will be famous long after he’s dead.

Does what you do now with personal training feel more real—does it feel especially real—or is it just the thing you’re doing right now?

I’m a… what do they call it? A fitness buff. I like seeing my clients getting thinner, stronger and happier. It directly impacts them. You can say whatever you want about working the wonders of the cerebellum. As a writer I have enriched people’s lives with my purple-ish prose. You know what? If someone can’t military press 30 pounds and a month later with me they can press 60, I did something. They had to put in the work, but I did something. They can do something they didn’t think was possible.

There are some of the people that I’ve trained who’ve gotten exponentially stronger, so much faster, because in the hour that I spend with them I don’t dilly-dally. I don’t waste time. It’s like, let’s squeeze an hour out that you’ll be feeling the effects of in two days. Your metabolism will be up. You’ll sleep better. Your appetite will be better, you’ll be hornier, whatever. That one always gets a laugh, but it’s true. Your testosterone level goes up.

Back to the original question: The talk. What has it gotten you?

It kept me out of a job I hated. There’s something to be said for that and I’ve told both of my sons, “If you do what you like to do in life and they pay you for it, your life is automatically well lived.” You’ll have health issues in your life, interpersonal relationship issues that will come and go. But I said, if you like doing something and you support yourself with it, that’s heaven. Most people can’t say that. What do they do? They go and work in a cubicle, in front of a Mac or a laptop or a tablet, and they do something that’s disconnected from their lives.

They can’t understand—and this kills me when it happens—Covid happens, everybody has to telecommute. We can’t go into the office because we’ll all kill each other, right? That passes, pandemic’s been over for a while and they can’t get people back into the office. Why? Because people don’t want to go back into the office. They’re just as productive as they’ve always been, but the boss wants to see the serfs rowing the boat.

Live in the Los Angeles area and want to work out with Johnny Angel Wendell? Check him out on Facebook. His personal trainer rates are more than fair.

"Alt weeklies mattered. That more of their great American journalism isn’t available online is indefensible."