Lance Tooks sketches, far from the blast radius

Consume the fruits of this Madrid-based artist’s first-ever Zoom call

‘Living in Spain, you definitely see that the politics here is not that much different. It's just that America, I always call them the elephant in the jacuzzi. It's like you're in a hot tub having a nice little hot tub party, and there's one elephant gets in there and starts splashing around, and there's no room for anybody and no water for anybody. Well, that's kind of what America does.’

Before we jump into my easygoing West Coast Sojourn conversation from Spain with graphic novelist Lance Tooks, I want to make sure you caught my Wednesday Q&A in

’s Oldster Magazine.I gave a lot of thought to some excellent questions about aging. This inquiry kept me thinking about it long after I provided Oldster with answers.

But yeah, last month’s easygoing conversation with Lance Tooks ultimately left me jealous, because Tooks had the foresight to dream of another country as a youngster.

By the 1970s, this native New York City artist had a fascination with all things Spanish. That’s when he discovered Warren Publishing’s macabre black-and-white comics, which were drawn by Spain’s greatest artists working in the medium.

“Here is room for a poem,” is the inscription translation adjacent to Lance Tooks

Miraculously, Tooks has come to live in Madrid and count his earliest influences among his good friends. Spain also seems to be outrunning the planet-wide fascism outbreak a little better than Stateside Americans are. So dude’s got that goin for him as well.

Jealous is the only word for how feel. Or is it envy? Like, which child among us dreamt beyond the culture that we were soaking in?

I should have done that!

Throughout the following exchange Tooks shares how drawing, animation, and sequential visual storytelling brought him to his present chill life. Tooks’ take on being a teenage editor at Marvel Comics is as realistic as it is succinct.

‘I first started working at Marvel and I was thinking, Wow, this place is amazing. All these people are adults, but they act like children. Then after a while, that kind of wore thin and it was like, Man, this place sucks. Everybody’s an adult, but they act like children.’

The tone with which we discussed the present political moment felt different, more sad and resigned than what’s common to me. In the moment, our talk was a necessary respite.

So. I am not proud that I hate on this artist for figuring it all out. But it’s uber-human to be wishing you had figured a way out of the coming shit show.

Our Q&A has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Donnell Alexander: Lance Tooks from Madrid, Spain, welcome.

Lance Tooks: Welcome to Madrid, Spain, because it feels like you’re right here, you know?

DA: Oh, that would be great, man.

LT: I’m a newbie with all this digital technical stuff, so.

DA: Do you mind me saying it? This is your first Zoom call. I guess my first question is, What kind of life are you living where you haven’t had to have a Zoom call?

Here in Spain, everybody handles everything with WhatsApp. I don’t even do phone calls as much as I used to. I say, “Meet you at this place” and I meet them at that place.

DA: Let’s work backward to how you got there. Let’s start with your life in The States. You come from an artistic family. That's an understatement, isn’t it?

LT: My daddy was a rock-and-roll singer back in the doo-wop days. And so he was with a group called the Genies that they had a hit record. “Who’s that knocking on my door?” Walla, walla, walla, bang, bang, bang, that kind of thing.

He was always recording because he built a recording studio in our basement in Queens. Basically was always working on commercial jingles. He was a composer in cooperation with my Uncle George. The two of them composed together under the names Lawrence E. and George A. Tooks. And the two of them would do all kinds of stuff. My dad was a painter, photographer.

DA: He put on some plays, didn't he?

LT: Theater producer…

He produced, he and my Uncle George composed all the music and we even acted in the plays.

Me and my sister were performers as part of the cast of musicals, which is basically what he wrote. He did one called E-Man, which was like an updating of Every Man, the medieval morality play that's been going on for a hundred, 500 years, probably.

And also one called Flat Street Saturday Night, which was about Allendale, South Carolina and based on a true story. A whole bunch of things over the years, and, as a result, all of his kids became crazy artists.

DA: How did you know that you wanted to work in the medium of sequential art?

LT: Well, the first [comics] I remember reading were in the recording studio where my dad was doing a session and somebody had them laying around. So I remember, you know, the Hulk and Sub-Mariner and Thor and all that stuff.

‘I’ve done some in color, but I don't see black and white as a handicap. For me, it’s like black-and-white movies: The shadows and the way that you light things can be kind of fascinating.‘

It was mostly Marvel that got my attention. And, of course, as a kid I liked Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, all that stuff.

DA: What was it about Marvel? This is like the early 70s, right?

When I was nine, I started buying comics myself with my lunch money. Then I'd make puppy eyes at the lunch lady so I wouldn't have to pay for my lunch.

Definitely about Marvel what I liked about it was that everything took place in New York. It seemed a little more realistic than the DC comics, which looked kind of like old people's comics to me when I was a kid. I don't know what the thing was, but there was so different about it.

DA:Was it just a matter of [DC] being past its time?By the 70s—and I was a little behind you—it just seemed like Marvel was of the moment.

Definitely, for me, it was that way. It looked like they didn't have the budget that DC had, but they had better, you know, stuff.

Of course, I really started getting into it when the Black superheroes started to appear. So, you know, Luke Cage: Hero for Hire, and The Black Panther, of course.

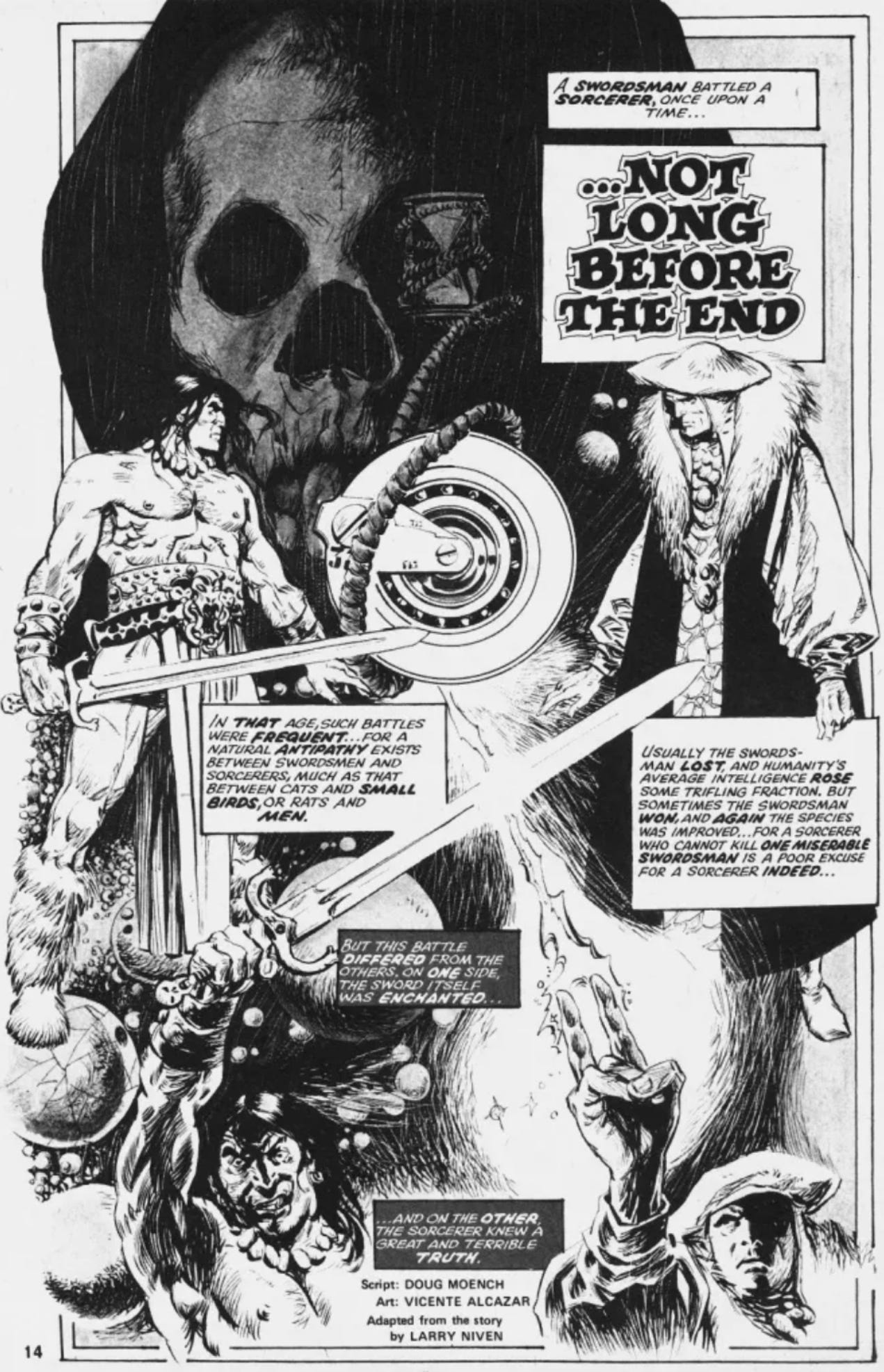

But the biggest discovery for me was around that time I started to discover the black-and white horror comics like Vampirella, Eerie and Creepy, which were published by a publisher called Warren. It had the best art, just like the best illustrations. And all of it was in black and white. That really kind of inspired me because I liked the look of these black m-and-white comics.

The wild thing about the 70s was that the majority of the artists that they hired were from Spain, and so that was something that really kind of provoked an interest in the country. I was always interested in Spain or Spanish in general, but there was something about all these artists. There was one named Vicente Alcazar, who’s since, since become a friend, and he did some just beautiful black-and-white artwork.

I’ve done some in color, but I don't see black and white as a handicap. For me, it’s like black-and-white movies: The shadows and the way that you light things can be kind of fascinating.

DA: That’s interesting. I’ll try to put the links to those comics so people at least have a reference to them. I got to talk to you last time a little bit about living the boyhood dream of working at Marvel Comics as a teenager.

LT: Oh, yeah.

DA: You can tell me the great stuff, but I'm curious to know what wasn't a dream about being in Marvel at that time?

LT: The biggest thing was that I first started working there and I was thinking, Wow, this place is amazing. All these people are adults, but they act like children. Then after a while, that kind of wore thin and it was like, Man, this place sucks. Everybody’s an adult, but they act like children.

And so that was the major handicap.

‘Being in the office meant that a lot of stuff was available to you, if you looked for it.’

The other thing was that even though I was young. But I was also kind of a precociously smart kid. I don't know that I’m a precociously smart adult, but when I was there I was so into it and put 100 percent into it the first year, because I was just enthusiastic about being there and I was there to learn.

I was hired as an intern. So basically I could look over the shoulder of Johnny Romita, who was one of the creators of Spider-Man. And I would take my 16-year-old feeble drawing and put it in front of him and ask him advice. And he would take a piece of tracing paper with complete respect and and put it on there and make his corrections on the tracing paper and say:

OK, you have to work on your anatomy because it’s clear that that doesn't go there.

And don’t cut the drawing off above the feet, because then everyone's going to know you have no idea how to draw feet.

And definitely things about storytelling, I got to hear it from the, the horse’s mouth, from the professionals that were actually doing it. That was the major advantage of being there, was I was there to learn.

DA: Tell me what it’s like going through an issue of a comic at the end of your career there as opposed to the beginning.

I was there for four years. I always call it “Marvel University” because I was there for the amount of time that most folks would have a complete stint at college. When I was 18, that’s when I became an assistant editor. And then when I was 21, that’s when I was forcibly ejected because my editor got fired and then I was stuck in a room with an editor who already had an assistant editor and I didn't get along with that editor very much at all. So basically my days were numbered. It wasn't my fault that my previous editor had gotten fired. It was probably my fault that I got fired, because I was kind of frustrated thereafter.

DA: Did you do Black Panther for Beginners?

That was probably a decade later because the entire time I was there, I didn't do that much actual work that I can point at in a comic. I could say, Well, yeah, I edited that.

I was working on The Avengers, and on all these big shot, multi-millionaire blockbusters are based on comics that I participated in while I was working there. But I wasn't as confident in my abilities as an illustrator, so I didn't really do much comics work. I mean, I did some backgrounds on an X-Men project, an issue of What If? that I recently sold—those pages—in order to finance a trip back to the U.S. The artist that I was assisting was Frank Giacoia. He's a classic Marvel inker. Being in the office meant that a lot of stuff was available to you, if you looked for it.

He was on a deadline. He needed to get this done fast. I did my teenager version of imitating what he was doing, and they printed it. I also worked on a Blade Runner adaptation, doing Zipatone and cutting together advertisements for it. I could pinpoint that as something from that time. But for the most part, I was not ready.

Immediately after working at Marvel, I worked in video stores for about four years and started to build my knowledge of film, because I wanted to be a filmmaker. Then after that, I found there was they were looking for a runner—a messenger—in a film production place called Broadcast Arts.

DA: What year are we talking about here?

LT: The video stores were 84, and broadcast was 87. So, Black Panthers for Beginners, I think was 94.

DA; When you weren’t ready, did you know you weren't ready?

LT: That’s the thing. I'm not sure if I wasn’t ready, because now that I look back at that work, I see things in it that I didn’t see when I was drawing it. I see the big picture now. I see that there were people there that were working on comics that weren't ready, but they’re getting themselves ready in front of the whole world.

And I could have been one of those, because I did have ability. Every once in a while, I’ll post something on Instagram or something that comes from one of my sketchbooks, drawings from 1980, I’m surprised. Like, Well, that wasn’t as bad as I thought it was, but I was very self-critical. Throughout the years of working in animation, I was still drawing all the time, but never completing a story.

DA: I took you off track. You were telling me about 1987, the company that you—

LT: Yeah. Broadcast Arts, which used to do a Pee Wee's Playhouse, uh, with Pee Wee Herman. They used to do all of the MTV station IDs that were really famous at the time, that were these little short animated things.

DA: It's a very famous company.

LT: Definitely.

And I think the best thing that they did was the project that I worked on.

I got hired as a messenger there, [to] get in the door. Then when you get there, find out what your path is. I was a messenger for a week and I showed them my artwork and wound up working on Madonna's film, Who’s That Girl?

West Coast Sojourn likes to get out of The States. Before SKA, conversation guests have included Antonio Olmos from London; Mike Wise and Ati Sundari (separately) from Mexico; Keith Knightfrom Germany; and Alexandra Marshall and Dimitry Léger, from France and Martinique, respectively. There is also, of course, the Legend of Black Mexico project

So the opening title credits where it’s like Madonna as Betty Boop? I inked that thing practically entirely myself because I was so fast.I was so excited about being behind a drawing board. And the way that I got the job was, basically being there—doing my messenger and doing my runs.

Sitting right next to me as a messenger at the same time was Rob Zombie, who went on to have a kind of illustrious career doing whatever it is he does. But we never really spoke to each other.

DA: He’s made at least one classic horror film. I think it’s The Rejects. The Devil's Rejects.

LA: I have that trilogy, actually. I enjoy those movies a lot. But, yeah, we never talked to each other. All I knew was this big hairy guy with a top hat sitting there and running errands.

When I was at Marvel, I’ll backpack and then go right back to this, but at Marvel, I paid a lot of attention to John Romita and also to Marie Severin. Marie Severin is one of my favorite cartoonists, maybe my favorite of all, because she was a brilliant colorist. Her brother, John Severin, was another brilliant cartoonist as well, who I was a big fan of.

Marie would let me just watch her over her shoulder while she’s working. The two of them told me two things that I never forgot about creativity, which is that if you want to be better at anything, you have to do it every day.

You have to draw every day and you will get better as an artist. It’s inevitable. If you want to be a great chef, you cook every day. You want to be a great race car driver, you drive every day. But it’s repetition where you learn.

The other thing that they taught me which sticks with me is that it’s not what you put into a drawing that makes it a good drawing. It’s what you leave out. Which is very minimalist and very Picasso and very Miles Davis. That’s the key for most of my favorite artists. So I’m never going to be a guy—even though I admire artists who have the patience to take hours working on a project…. I try and do it as fast as possible. My ideal would be that it looks like the ink is still wet because it’s done very, very quickly.

They encouraged me to do those things. And the way that I did those things is I started to fill up sketchbooks. While I was still there, I started filling up two sketchbooks every year and have done that since 1980, 81, 82–around that time—which means I've got an encyclopedia of sketchbooks, with numbers on the margins. There's more than 80 volumes.

I was asked by the librarian at Columbia University to donate my and I’m planning to do that. I’m in the process. It’s been a slow process, but I’m about to speed it up to try and get this done by the beginning of next year.

DA: I’m just curious, because I don't know anyone who’s done anything like that. Why would the process be slow?

LT: Because I want to keep my artwork, which means scanning it into a computer.

Scanning in 85-plus, 90 volumes of sketchbooks is an arduous, repetitive task. I mean, I realize I'm old enough. I could probably hire some young person to do this work for me.

About the sketchbooks, when I went to and saw they were working on Madonna's Who’s That Girl? they had all these storyboards and images of the character who, it’s Madonna designed to look like Betty Boop. It was a real cool style [by] an Argentinian animator and cartoonist named Daniel Melgarejo, who’s passed away.

He actually was standing there and I showed up with my 10 volumes of sketchbooks, including drawings that I had done that were, caricatures, making fun of Madonna. And this was when she was new. But all kinds of things, a variety of different things. I’m standing there and everybody all around is looking into these books. I stopped being a messenger that day.

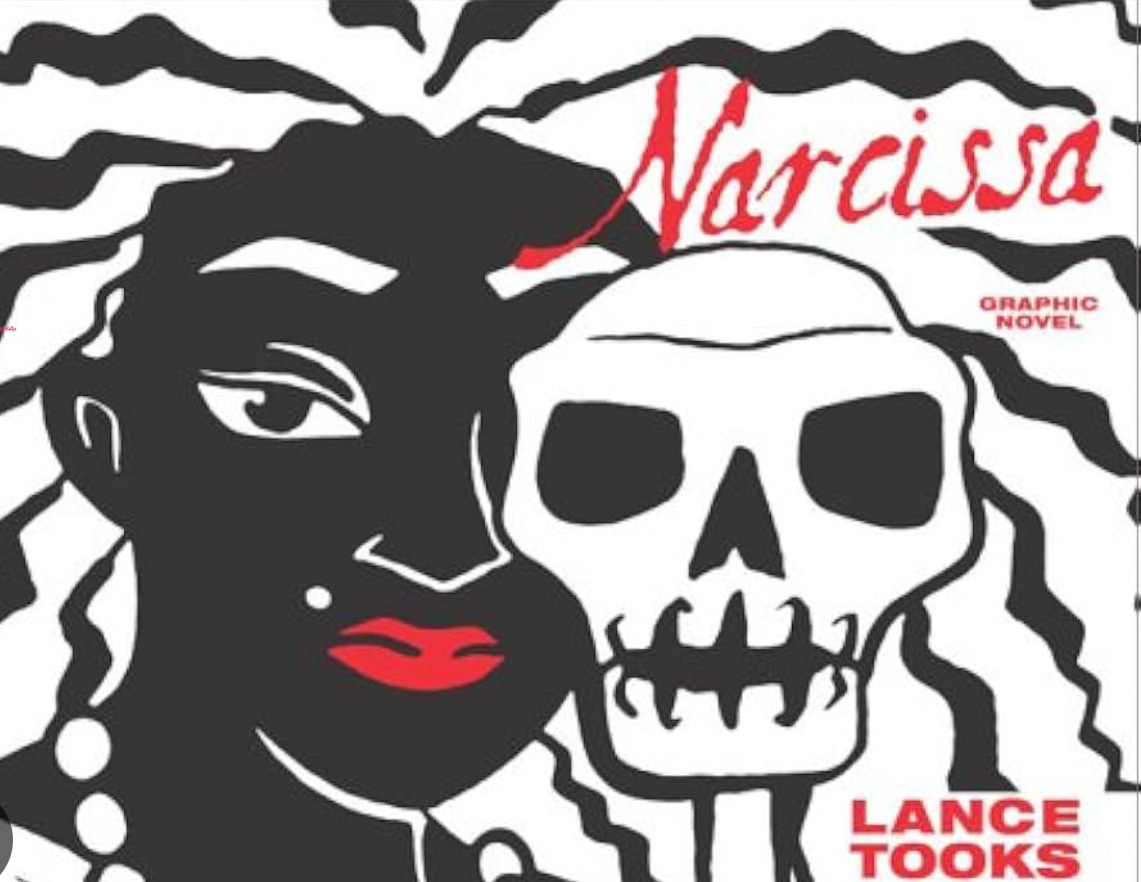

So how do you get to Narcissa?

She’s there behind me on the wall. That’s actually the back cover of the Spanish edition, which I wound up translating myself and was published here in Spain by the government in Granada.

The original version was published by Doubleday Random House. The editor who I owe the project to is Deborah Cowell, and she was just remarkable.

When I was working on the Black Panthers book back at Writers and Readers, maybe almost a decade earlier—get the time span wrong all the time—that was her first job working in publishing, at Writers and Readers. They were famous for doing a series of books for beginners, like Marx for Beginners, Mao for Beginners, Miles Davis for Beginners, and Black Panthers for Beginners. And so that's the one that I wound up working on with the historian Herb Boyd, who's done a lot of work—and keeps doing the work.

DA: Herb Boyd is still alive? I didn't realize that.

LT: Very much so. I did a cover for him about the Black Panther movie, which mirrors the images for the cover of the Black Panthers for Beginners. The same color scheme and everything, but it’s basically a group of essayists and political thinkers basically discussing the Black Panther movie of Ryan Coogler, the Marvel movie. I got to draw a Marvel superhero in color for the first time and have it published. That was only just a couple of years ago.

But Debbie Cowell, she wound up rising in book publishing. She was the editor of Michael Chabon, of Jonathan Franzen, a lot of folks. In a very brief time, kind of made a dent in publishing. And she was the editor of me.

Around 95 is when I started working at MTV Animation, doing background and inking mostly. I was known for the line quality that I’ve kind of developed in my sketchbooks or whatever. There was another artist that she was working with named Jason Little, who did a bunch of graphic novels as a professor in, I believe, visual arts or Parsons School, She said she's been looking for this artist, Lance Tooks, who had worked on the Black Panthers book. But she hadn’t been able to find him.

And the guy said, Well, he’s in the cubicle next to mine over at MTV, working on Daria.

DA: So you worked on Daria.

LT: I worked on on a lot of kids TV after the Marvel period and then after during the animation period, I worked on a hundred TV commercials, TV series, music videos, just a whole mess of stuff. And it was always changing my style depending on what the project was. That also is something that contributed to me improving as a cartoonist, having a challenge every month. Everything had to be either.

At the time, it was like, “We want something Simpsons-esque.” Or, “We want something Pee- wee Herman-esque,” You know, they just add “esque” to the word, and that whatever was popular at that moment. That was kind of fun for me and kept me fed.

DA: Well, we’re going to get to Narcissa, I can tell.

‘I wanted to make a soap-opera/melodrama kind of story. I love that you can use the fact that people are familiar with the idea of the story, and then you can subvert it in various ways.’

LT: Oh, yeah, definitely.

So, Debbie Cowell, we got in contact with each other while I was at MTV, and, basically she said she’s starting a line of graphic novels. And one of them was Jason’s one. And one of the other ones was by Will Eisner, the comics giant, creator of The Spirit and maybe some of the first graphic novels were done by him.

She said, what do you want to do? And I said, Narcissa, because I figured I'm going to get one shot at this. I always talk about how How Stella Got her Groove Back was a landmark in cinema, even though I was wasn’t a fan of so much of the movie. But it’s the first time in a hundred years of cinema that a Black woman took a vacation. So I wanted to do a travelogue story about a person on the run or wanted.

DA: Her circumstance is different from Stella’s, right?

LT: Oh, absolutely.

DA: She's a filmmaker and what's the inciting incident?

What happens is that she finds out she's got a terminal illness, because I wanted to make a soap-opera/melodrama kind of story. I love that you can use the fact that people are familiar with the idea of the story, and then you can subvert it in various ways.

“As the world turns” is the very first line that she says, which was the name of a famous soap opera. The whole idea is that she has this illness, which the doctor determines is terminal because she’s in the middle of making her film and has what appears to be a stroke. She passes out on the bus and winds up in the hospital. It’s all very vague, what she’s actually got.

I’ve always said—but never publicly—is that she's got acute Caucasianitis. That’s what's actually getting in the way of her completing her project, completing her vision.

DA: What does that mean in this particular context?What are the symptoms?

In this context, well, symptoms are impending death. And so, she runs off to Spain because she just runs to the airport. She takes the first bus out of the hospital after grabbing her clothes. She’s working on a film and she’s got to complete this thing, but she’s had to work uphill because the independent producers that had agreed to produce it, they stick her with this producer who’s basically a white producer that produces Black people’s movies.

‘I wanted to do kind of a mystical book with an atheist in the center of it.’

DA: Doesn't he get her to change the title to something ridiculous?

LT: Well, he wanted to call it, Get Jiggy with It. And actually the working title of her film was Shadows Have I. The story even starts with a nightmare that she's having, where she’s seeing all of these characters that she has been loving and nurturing being turned into stereotypes of various types.

There's the whole gamut of the magical Negro, which was a new phrase that I thought that I had patterned for the first time. But, I guess, what else do you call someone like that?

And there were a whole bunch of them. There was the Black character that throws himself on a grenade to save the White man, the hoochie mama character…

DA: I always enjoyed calling The Magical Negro Yoda for White People.

LT: Exactly, exactly.

DA: I’m sorry, I interrupted you.

LT: Then there's the cop and his flashy sidekick. You know, the White cop and the black cop is the sizzle. But the White cop is the steak.

Basically, there's a rogues gallery. It was a fun book to work on. It took a year to do it. Halfway through working on the book, September 11th happened, which was kind of crazy.

DA: Same thing happened to me, dude. I was literally going to the publisher the morning of September 11.

LT: Wow.

DA: I'm sorry, my agent was going out to publishing houses. I looked up at that building, I said, this is going to fuck my book. That's my lasting memory of 9.11.

LT: Among the moments of working on Narcissa, Narcissa, the character, is an atheist. I wanted to do kind of a mystical book with an atheist in the center of it. Her character had evolved before September 11th even happened. But at the very beginning of it, there's a part where she's on the airplane going to Spain and she meets an old woman and they have a kind of debate about religion and it gets so frustrating for Narcissa.

She goes into the bathroom and she says, I should just go. She considers going into the cockpit and taking it over and steering the plane into that big, stone Jesus in Brazil. But then I got to know Narcissa. She would never do something like that or even say something like that.

Then someone actually did take control of airplanes and use them to take down iconic buildings or whatever. I’m glad that I’d already changed my mind about the kind of character that she was before that ever happened.

DA: If I understand right, the book came out, you thought it had kind of gone away and it got kind of found later. What is the history of it? What happened?

LT: The history of it is that the book came out and Doubleday—who spends most of their money promoting their authors that don’t really need promotion, like Stephen King and John Grisham—they did no promotion whatsoever on the project. I always accuse them of leaving the books on the beach for seagulls to eat.

‘I did a series afterwards for NBM called Lucifer’s Garden of Verses, and they were four volumes that were each stories about the devil, who I picked because that’s a character everybody knows, you know? And now I question the wisdom of having done that, now that the U.S. is trying to convert itself into a theocracy.’

There are people who remember, and I do get letters from folks and stuff like that. I don’t know what the effect of it was. There were things like in Chicago, there’s an artist, Tertel Onli, who has been working on independent comics with Black protagonists for years.

And he organized a sisters talk about Narcissa, which was entertaining, in this little youth center in Chicago a decade ago or more.

DA: It’s a singular experience to have something that's like a cult book anyway? But what is your experience as a creator who’s had a Black cult book that you know was good. It exists in this realm outside of the commercial mainstream. You hear from people. What’s that experience like for you?

LT: As my dad would say, I wish it was money. [Laughs]

You know? Thanks. I wish it was money.

But in this case, it’s an honor. It’s a privilege that somebody remembers something you did. I’ve got all my books that I’ve loved on my shelf. And so someone has that book in their household.

It wasn’t all positive reviews. I mean, the only main real review that it got in a comics publication was from the Comics Journal, and they despised it. I mean, they really hated it.

But other folks have been more appreciative, especially as the ones that were most positively received [when] I did a series afterwards for NBM called Lucifer’s Garden of Verses, and they were four volumes that were each stories about the devil, who I picked because that’s a character everybody knows, you know?

And now I question the wisdom of having done that, now that the U.S. is trying to convert itself into a theocracy, who am I going to sell these thousands of boxes of books, four hardcover volumes of the devil? Who am I going to sell these to?

DA: It’s going to take a little longer to become a theocracy. After the civil war. After we lose the civil war out here . [Laughs, nervously]

I don’t know if you're following that closely but the [West Coast] states out here, they're having special legislative sessions about how to protect themselves against the president. That’s exactly as crazy as it sounds.

I had a couple expats most recently on the podcast and we were talking about whether it was a crazy idea for me to ask whether they would ever come back.

My friend said, That’s just the stupidest question ever. And the other one said, When you live outside of America long enough, you see that America is anarchy. And I’m curious to know from the comfortable city of Madrid, how you were looking back on us right now.

LT: Well, I mean, the way that I look at America is I love America. You know, it’s the place where my mom lives. It’s the place where my sister is. I have two nephews.

DA: That’s your baseline approval.

LT: Yeah. That America, scrambled, messed-up America has always been there, Living in Spain, you definitely see that the politics here is not that much different. It's just that America, I always call them the elephant in the jacuzzi. It’s like you’re in a hot tub having a nice little hot tub party, and there’s one elephant gets in there and starts splashing around, and there’s no room for anybody and no water for anybody. Well, that’s kind of what America does.

In general, this lean to the right is everywhere. It’s all over Europe. It’s all over all kinds of countries. I think the next regime in Spain is probably going to be leaning more in the direction of fascism, especially with the inaction of the politicians during the flooding that recently happened. It’s not looking good for the current administration, who was kind of, wishy-washy, centrist party candidate.

Like, Joe Biden’s everywhere, you know?

I think, you know, things are getting hairy everywhere, basically. And a lot of these politicians over here that want to be Trumps. They model themselves after Trump. I saw there’s one in Venezuela that’s popped up that has the same stupid haircut. It’s like a plague and it’s spreading.

You know, you can’t get off the earth. That’s the only way you’s be safe. [Laughter]

DA: Yeah.

LT: Hurling bombs at each other, you know.

DA: We’ve had a lot of conversations, my friends and I, about what fascism looks like. And I think it’s maybe a very comfortable kind of fascism in the sense that there aren’t going to be detention camps. But just mentioning again the sort of targeting of California. California is going to get a little bit worse culturally,

They’re already they're shutting down DEI, the diversity and equity programs. That’s happening so fast. Walmart shut those down immediately.

LT: Yeah, that’s no surprise with them.

DA: I hate to go out on that note man, but we need to be wrapping it up. Tell me what your days are like. How do you work these days? What what’s it like?

LT: I sketch a lot in bars, because uh my apartment's so modest. I found I’m comfortable in a bar sitting by a window with whiskey in one hand and a pen in the other. That’s kind of been my routine for over a decade now.

I’m actually kind of working on an autobiographical book. The title is inspired by something that my mother called me over the phone once, but doesn’t remember. I thought it was genius and said, I have to use this.

It’s called Memoirs of the World’s Fattest Starving Artist. And the thing behind it being that she might be worried about her baby who’s so far away on the other side of the planet, But she’ll see a picture of me online and say, “Well, at least he’s eating.”

If you’ve made it this far…

…you’ve had a substantial experience. Please consider leaving a tip. Or, perhaps this read is the one that cumulatively puts you into first-time tip territory? You would know if you were there. No foolin’

Great interview...muchas gracias!