RJ Smith and the fraying country that lives in us

A move from Echo Park to Nashville has the iconic author and critic in a new mode

As much as I loathed the New York sports writing scene, I loved being a LA music journalist in my youth. The free shows and free music and access to your heroes was every bit the privilege you’d think it would be. Even when the artist sucked as a person. Even if they had bad breath or body odor. To know for real and not have to speculate is a privilege.

Because the heyday of my work happened in The Near Olden Times, record labels sent me lots of CDs, advance cassettes, and vinyl. Most of it was crap, and once a month I’d haul the music I didn’t love to a physical record store like Rockaway and maybe get a couple hundred bucks. LA Weekly paid more in freedom than in competitive wages, so this particular perk was treasured.

To write about music is to write about the world.

The absolute best was hanging out with my friends who wrote about music. There was P. Frank Williams and Tracii McGregor, who would go on to do executive editor stints at The Source. The great Ernest Hardy. Sara Scribner… critics were around me all of the time. Manohla Dargis edited my film stuff.

Critical thinking about the culture I consumed was the daily rule, not the exception.

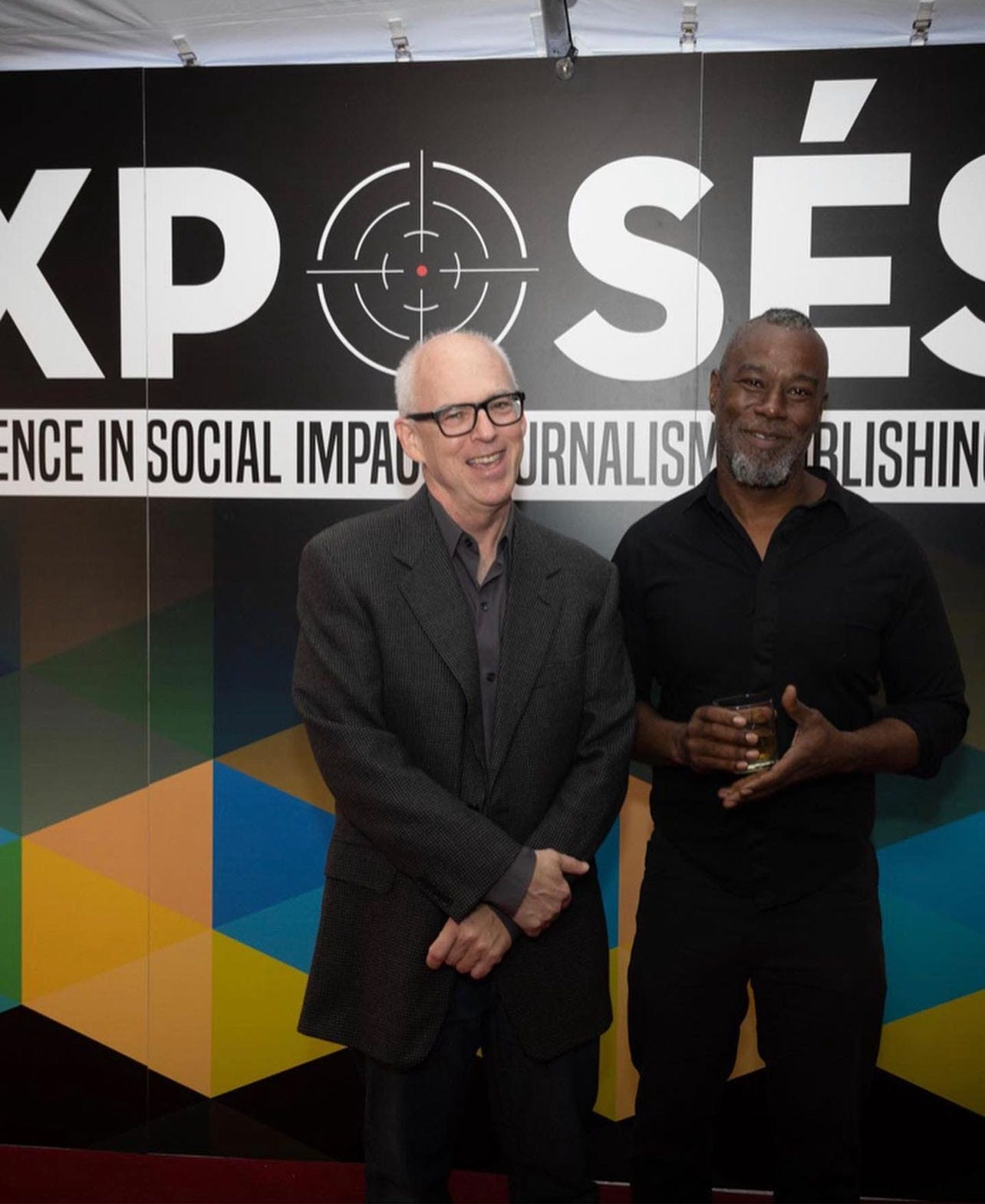

Probably the most accomplished of all the writers in my circle was and is RJ Smith, who is freshly arrived in Nashville. He’s taken a gig at The Country Music Hall of Fame, and I have so many questions about that.

An erudite scholar of American pop, Smith has tackled Chuck Berry, James Brown, and Robert Frank as an author. Yet, he’s also a dude I would call up to go see a Dodgers game. When F. Gary Gray’s Friday came out and RJ didn’t see in that flick the timeless classic that I saw, I reveled in not letting him forget it.

What follows is a lightly adapted version of the conversation we had two mornings after the Super Bowl. Hopefully you make it down to our brief discussion of this week’s Pop Conference. I recommend the Zoom version of our exchange, but reading is fun, too. Enjoy.

Donnell Alexander: I’ve been lucky to be around a lot of great writers in my career, but this is one of the most respected people I know. Because I am a music critic I admire the hell out of RJ Smith. Welcome to the podcast.

RJ Smith: Donnell, it’s great to be here. Thanks for having me.

DA: It’s fun to get my energy up. I’m genuinely excited to have you here. You’re in Nashville.

RJ: I’m in Nashville, Tennessee, moved here about seven months ago. Still getting the lay of the land, but it’s been good so far.

DA: Back in the nineties, we were in LA, in the Good Luck Bar. What’s the movie theater it’s by?

RJ: Oh, The Vista, which Quentin Tarantino owns now.

[Chuck Berry]’s someone we think we know, either as a human being or definitely as an artist. The truth is that the more you listen—not just for me, but for everybody I’m sure—the more we can hear.

DA: That’s right. What I loved about that bar was that it would take on the character of whatever movie was showing that night. [Laughter] You would see that in New York sometimes, but not so much in LA.

Anyway, I said your name and the guy next to me said RJ Smith?! He was just really stunned. This guy was a musician. Why do you think musicians—why do people connect with you as a writer, period?

RJ: I don’t remember who that was, but somebody told me once that… I’d written a review of Dave Alvin—speaking of Los Angeles, Southern California musicians—and I said what I love about Dave Alvin and what was the problem with a specific recording-release of his. Through a friend he communicated to me that he really appreciated that piece—which was not a favorable review, in some ways—as the rare time when he learned something useful out of a review, much less a negative review.

I don’t know what that even means, but it was wonderful for me to hear. You know, finding ways to offer input, criticism, to use my voice in ways that are not insulting to readers or musicians. Sometimes I hit that target, sometimes I miss it.

But yeah, it’s great to connect. And music is amazing; to write about music is to write about the world. I’ve been lucky to have a lot of great readers over the years.

DA: That’s very humble. You have to be an excellent writer, but you also have to be a really good listener. I’ve told you before that I’ve thought of you as someone who has really good ears. Is that something you had growing up? In your household, was music around? Who were your influences and what did you listen to?

RJ: I grew up in Detroit in the sixties. Radio was always on at my house. It was just the background; my parents played it all day whether they were listening or not, so I’d hear the Metropolitan Opera on weekends and The Grand Old Opry on weekends and the lounge shows during the day—just whatever was on. That turned me on to top 40 radio, which I played in my room. And top 40 in Detroit played everything, from Motown to acid rock, the MC5—their 45s—and maybe country like Kenny Rogers, stuff like that.

It was all mixed together—Motown, soul, funk, a lot of 45s. If it was a hit in Detroit, they would play it. And Detroit had big ears. So I’ve got Detroit ears.

DA: You know, I grew up on Lake Erie, in Ohio. Sandusky, Ohio. And I listened to CKLW in—

RJ: Windsor!

DA: And the mix was pretty amazing there. Those stations had to be influencing each other, it was such an amazing time. I realized only after the fact that most of the country didn’t get that.

RJ: We know that we were lucky. That was just like, “Oh, this is pretty good.” Like: Comic books, top 40 radio—this is all working out pretty nicely!

DA: I’m stuck on the subject of how you listen to things. Your latest book is about Chuck Berry, and I can’t help but wonder about someone like that—who you’ve listened to your whole life—how do you listen to him anew?

RJ: Wow. Well, I’ll tell you, he is someone that I listened to anew.

He’s someone we think we know, either as a human being or definitely as an artist. The truth is that the more you listen—not just for me, but for everybody I’m sure—the more we listen, the more we can hear.

Also, I think there’s nothing like having a deadline, as a writer. [Laughs] When you have to say something new about somebody? You start listening for something new. Oh, my God. It’s amazing what you can pull out of your ears. Or, somewhere.

DA: I don’t know if we’ve ever talked about this, but one of the things I came across in college that really affected me as a writer is an interview with Lyle Lovett, who went to journalism school. In Texas, you know? And he said the liberation of the deadline is something he depends on. That obstacle in front of you just forces stuff.

RJ: I wish I didn’t need a deadline, but it’s huge. When you’ve got two hours or two weeks and you’re working—you’re thinking. But when you’ve got that blank page, you just start putting nonsense in there. Then something good comes out of it, eventually. Yeah, I wouldn’t get anywhere without a deadline.

DA: One last thing about the Chuck Berry book. You wrote this great book about James Brown, and James Brown is someone who stylistically had so many different phases. And I know that it’s not comparable to Chuck, who had a great burst at the beginning of his career. How is it listening to him anew when there wasn’t necessarily a rich landscape?

RJ: Listening to Chuck?

DA: Yeah.

RJ: With James Brown I feel like there’s so much mystery in that music. There’s just so much to it and it’s just bottomless… and it’s not that Chuck isn’t bottomless, it’s just more concise. And the pallet is narrower. And the words are specific, so you start listening in a different way. You’re aware of the smaller set of tools. To me, that’s elements in the work. And how did he make a restricted set of elements—Chuck versus James, say—do so much.

There just seems so much to say about this country that’s living in us and the music that comes out of it.

DA: What’s it like going from black music to country music? There’s obvious overlap and all of that, but what’s it like?

RJ: That’s a great question. They told me they had a job listing last summer and asked me if I was interested in applying and I said yes. From the beginning I said that I’ve listened my whole life to country music, but I haven’t written about it that much. What I like, I like and what I don’t like I’m really not an expert on at all. And because they are brilliant people—and being very nice to me—they said, “We get that. We know that. And we want what you do.” So that’s cool. But I’m learning. I’m learning in this job.

DA: At our age, that’s all you can really ask. That’s a great gig if you’re learning and they’re payin’ ya.

RJ: So I had this idea that I wanted to start writing about country music and all of this stuff, keep writing books and whatnot. There just seems so much to say about this country that’s living in us and the music that comes out of it, in terms of country music. And the way this country is fraying at the seams, maybe in a way that is reflected in country music, talking about race in country music.

This is going to wander off the subject a little bit for you, but I’ll just put it on a tee for you and you can just edit it out if you want. I’m going to be on this panel of music writers talking about country music criticism, in March for the annual Pop Conference of music writers and academics. We were trying to figure out, what do we want to say about country music criticism.

In the time that we’ve been working on this proposal, so much of music journalism has gotten destroyed, just in the last six months. The ability for music writers to make anything like a living has been diminished. So we’re thinking, maybe we’ll just sit around and talk about Beyonce and country music. That’s more forward looking. More optimistic, maybe? I don’t know. We’ve got to figure out what we’re going to say.

DA: That was next on my plate: Beyonce. It’s two days after the Super Bowl. I’m in Vegas, I’m thinking Super Bowl [when she announced a forthcoming country album]. What did you make of all that?

RJ: My feelings about it are complicated. I’m really eager to hear that whole album, which I guess is late March, at least the current date. There’s so much to be said, in terms of race and country music, in terms of artists like Jason Aldean and Morgan Wallen, in terms of the roots—how Black they are. There’s a lot there.

My feelings about Beyonce are complicated though, because I, um… I like reading about her. And she’s going to inspire a lot of great criticism, I hope, with this album and with this subject. But I can’t say I’m a huge fan? I feel like she’s good at what she does. I’m glad she’s there. She’s a force for goodness. But I’m going to have to do some listening, deeper into her, if I’m going to use her as a subject.

DA: I hear the country in her. It’s one of the things I find interesting. I’m not able to pick off the top of my head an artist for whom this might seem calculating? But the Houston aspect of her singing is very much rooted in that tradition.

I did some documentary work that’s never going to come out about this amazing artist in Sonoma County who’s reclaiming the banjo as a Black instrument. And the way she plays it is completely unpredictable. I love it.

I’d love if there were some sort of inflection point where we’re really going to look at country music. I lived on Lake Erie, but my grandparents are from West Virginia, so we watched Hee-Haw. I know we’re not alone. The Black Junior Samples fan club is bigger than you think.

[Laughter]

Just wanted to make that joke. I was not a big fan of Junior Samples.

The last jokey thing I have to say is that I imagine the Country Music Hall of Fame thought you were Black and that your hiring was intended as some sort of Black Lives Matter thing.

RJ: See, that’s the pre-Internet era. One thing that I stumbled upon that I instantly liked is that with a name like RJ Smith, your gender, your identity, it is to some degree whatever the writer wants it to be. So, when I was writing for the Village Voice in the 80s, whatever I was writing about they kinda thought might represent that audience or that identity, I guess. [Laughs] In this case they knew exactly who I was; they’d seen my author picture.

DA: I am joking. I do want to ask you about Nashville, as a place. I have limited experience with it. My son worked there a couple of years ago and spoke very highly of it. You’re a rookie, but what’s your impression of that place.

RJ: It’s pretty friendly, and that’s good. That’s that Southern thing, to be all cliche about it. People tell me it’s The Southern Thing, you know, of people reaching out to the newcomer. And that’s been great, just the conversations I hear in lines at the bakery or for coffee and being invited into that. It’s a welcoming place, and that’s been great. Great food town.

Great music town, and what’s great about it as a music town is, there are people who hate country music here, but they like Norteño, or reggae. Or, country music, (what) it means to them, it died in 1938, so they’ve got this whole vision of it that’s completely not about what’s on commercial radio now. This town is just full of music fanatics.

It’s actually been great to just be in the celebratory moment a lot, where people want to share what they’re listening to. They want to know what I’m listening to. They want to talk about it in this loving way, and maybe I’ll get tired of it eventually. But I’m loving it now. It’s kind of therapeutic after having Chuck Berry live in my head for five, six years.

Coming off of writing about amazing, gifted musicians, but haunted human beings like James Brown and Chuck Berry, it’s actually been great to just be in the celebratory moment a lot, where people want to share what they’re listening to. They want to know what I’m listening to. They want to talk about it in this loving way, and maybe I’ll get tired of it eventually. But I’m loving it now. It’s kind of therapeutic after having Chuck Berry live in my head for five, six years.

DA: A pallet cleanser, at minimum. What do you miss about LA?

RJ: The mountains are all on the wrong side here. I gotta work on that.

I miss the beach. I miss being able to go from the beach to the desert in a day. That’s cool. I don’t miss the traffic and it just got worse over time. People complain about traffic in Nashville, but they have no idea.

As you know, there are so many kinds of people. There’s a way in which categorically it’s diverse. But the way people live it is so not diverse. Or, my experience was. So, I guess I love the promise of LA and I don’t love the reality of LA, in a lot of ways.

DA: What’s been the biggest adjustment?

RJ: I gotta think about that. On a personal level, making friends. Just feeling like I have a social life. I’m workin’ on that.

In LA you’ll have 20 Mexican restaurants or record stores or book—well not book stores so much—six book stores—whatever you are craving, there’s a lot of ways to get it. There’s a lot in Nashville, but it’s a third or a fifth of [Los Angeles]. It makes it easier—your options are a little smaller. But there’s a little of everything here, so that’s cool.

I miss the range of possibilities sometimes, yeah. And museums.

DA: There are very few cities on the planet that can compete with LA in terms of that.

I wanted to spend the rest of out time talking about country music in the context of these times that we’re in. They’re so fraught. Even with the Beyonce stuff, I think there’s a canniness to that decision. Country’s always been popular with the right wing, but does it feel like a weird time to be a fan? Are artists making gestures to be more mainstream? To reconcile?

RJ: That’s a rich question and my answer is unfolding as I unpack it.

DA: It was a pretty long question.

RJ: It’s a good question though. I think I’m going to get something really good to write about and think about as we go through this next election cycle, we go through the next few years after that—and just going forward way beyond whatever the election cycle offers. And I think the relationship of the music and the political sphere is so complicated and telling with country music—on all sides—that it will be a great subject for me as a writer. And I hope we survive it. [Laughs]

DA: Have you seen Killers of the Flower Moon? Is that Jason Isbell in a part?

RJ: That is. Sturgill Simpson is in there a little bit. Jason Isbell. A couple of other musicians, but Jason Isbell has a part. He’s got actual lines.

DA: Did you think that he was good?

RJ: I didn’t love the movie. [Scorcese’s] heart is in the right place. And it’s a story that I liked seeing in a movie and wish it had been told much more through the people most involved, most affected by that history. But [Isbell] is good, he’s good. He just got his teeth fixed, I was reading on the Internet. So, I think maybe he’s going to some more parts in Hollywood. [Laughs]

DA: When I think of him I think of country artists who are more on the side of good, who are trying to educate their people. Is that a trend? Do you see other artists like that who are not necessarily distancing themselves from the hard right aspects of rural life, but just emphasizing the commonalities?

RJ: Yes, and they get relegated. They don’t get played on the radio. I mean, Isbell’s a star. He has a huge audience, but I don’t know that he’s getting much play at all, on radio say. And there’s any number of people that are very popular in so-called Americana genre or category, which is a little different from country. But we could argue for weeks about how it’s different, except that Americana doesn’t get played on big, commercial country radio. And country does—whatever you define country as.

And I imagine, sometimes I think the artists we think are right wing aren’t always right wing in person or in private. And the ones where they go left wing aren’t always left wing. It’s more complicated than that.

DA: What was it like there when Toby Keith died? Were flags flown at half mast?

RJ: It was a big deal. Yeah, people are still.. at the Country Music Hall of Fame we print obituaries of people like Toby when they die, of course. And to read the responses of fans and musicians who responded on social media to what was posted was good for me to see and gives me a lot to think about.

DA: We’re like 20 minutes into this and we haven’t said the name Taylor Swift. It’s just kind of remarkable. She comes from Americana. I have a girlfriend with an 18 year old daughter and I hear that music. I’m not going to say that I can track the entire evolution of it, but… do you still hear the Americana in her pop?

RJ: One thing I think that is definitely true of country music—maybe even more than Americana—but it’s certainly overlapping and it’s certainly there with Taylor Swift is the emphasis on craft. Not always three-minute craftsmanship, but largely so to some degree. Hit making and making a few words say a lot. Making a few notes and a melody that 10 different people have worked on to be as effective as they want it to be.

I don’t even know why that’s necessarily country, but there’s a certain approach to craftmanship that I feel is really true of Taylor Swift and country music. She would still say she has one foot planted in country music and has very much been prominent in the city here. And some of the instrumentation and some of the songs are more country than others in recent releases.

There’s an ongoing conversation about what is country—who is and who isn’t, you know? And it all depends on… well, I don’t know what it depends on. But what you like about country music defines who you think fits that bill. Some people say Jason Isbell isn’t. Some people say Taylor Swift isn’t.

But a lot of people say what’s on commercial country radio isn’t “real stuff,” isn’t the classic country that they crave. So, yeah. It’s a big, messed-up, complicated, rich audience.

DA: I was thinking about the Grammys and Jay Z’s speech, which was about rappers not getting their due. I’d read there are as many Americana Grammy voters as there are hip hop. (Read inside of the numbers.) So you’re never going to get to a place where Album of the Year is going to be representative of what’s going on in the culture.

I’d lost my question, but now I’ve found it: You’ve lived in a company town on the West Coast and you’ve lived in that one.

RJ: And Detroit!

DA: Yeah, but you weren’t really conscious in Detroit, right, of what you were in? These entertainment industry company towns—Nashville’s notoriously a company town—contrast the two. Do you see distinct differences in how one company town operates from the other?

RJ: In LA people are fairly open and attentive. You never know whether the person you’re talking to is going to be part of your next deal. You might be working for them, they might be working for you. So there’s always a little bit of openness. I’d say there’s a lot more of that in Nashville, and it’s not even about deals all the time—although it’s certainly part of it. It sorta overlaps with the Southern friendliness thing.

So LA has that aspect, but it’s also cooler and more judge-y. People pretend… not pretend—

DA: Maybe pretend. [Laughs]

RJ: Alright, alright. But do you know maybe what I was trying to say in a diplomatic way? Which is that people work on a couple of different levels at once in LA, where you know they’re sizing you up, but they’re also offering you something maybe. Or are open to your ideas seemingly. And it’s a little less sincere than maybe Nashville.

DA: When you go to cocktail parties or maybe barbecues, do you see the business happening?

RJ: I haven’t been to enough yet. I gotta work on getting invited to more stuff. It’s everywhere. Gosh, I work at the Country Music Hall of Fame and you hear about it, see stuff. And everyone is always thinking about their deal, or their record or their audience.

Every Lyft driver I’ve had—not every one—but when I talk to them… they’ve played at The Opry. The guy that was a drummer is driving a Lyft. He’s played at The Opry 40 times. But he can’t make a living as a drummer. Grand Ol’ Opry 40 times. It seems like everyone potentially has one foot in the business here. Or has someone in their family who is. So, everyone’s playing the game a little bit here.

DA: It’s funny. When I read that you were doing it… it’s not that I didn’t think country music was in your wheelhouse, it was just such an unpredictable move. I just had to say that before I go. It’s remarkable.

Before I let you go, I want to know what you’re listening to deeply?

RJ: Wow. I’m going to have some really good answers for you… when we get off here. What am I listening to right now, that I really like?

There’s a great guitar player that I’m looking forward to seeing at The Big Ears Festival in March, and I’m spacing on her name. She’s on Nonesuch... Mary… I’ll look her up as we’re talking…

DA: And I’ll stall for time. It’s hard because there’s just so much content that you’re kind of a specialist at this point. All of this stuff is floating around you. It’s hard to consider new artists, especially in depth.

RJ: Mary Halverson. She’s been around for 10 years maybe. She’s really great, sort of a modern improviser-guitar player. A lot of noise, a lot of melody. She plays with big bands, she plays with skronky, John Zorn-end-of-the-spectrum musicians. She’s playing, like, three or five shows at The Big Ears Festival. I’m a huge fan and I’m really looking forward to seeing her.

DA: The Pop Conference: Does that take on the mood of the industry? Or is it so academic that it’s aside from all of that?

RJ: You’re right on both counts. I think the ratio of unacademic writers who get paid for a living—sometimes get paid for a living—but aren’t teaching has dropped so precipitously. Some of those people—many of those people—have gone on to academia, although academia is having its own problems of culture and how much they value writing and music and American studies and stuff.

Yeah, that’s dipping, but what’s good about this conference at its best is it puts the academics and the non-academics, museum people, and some bands—some musicians—and they listen to each other. That’s pretty cool.

DA: It’s in the summer, isn’t it?

RJ: It’s been April every year for about 21 years, but it’s in March, at USC this year.

DA: The one I attended digitally, the same day I attended the California psychedelics conference, right around the corner from me, in The Arts District. They we were related, but there were different vibes between the two.