What makes Portland protest?

Scenes from the social unrest of 2020, illuminated by Rian Dundon’s new photo book Protest City

I know my time on the Former Twitter wasn’t fully wasted because Rian Dundon found me there and asked if I’d write the foreword to his new photo book about the George Floyd unrest in Portland. There’s a tad bit of hyperbole in that statement—the platform of that hellsite was indeed to die for—but not a whole bunch. Protest City is among my favorite projects to have been part of in a long, long time.

It’s dope that Rian talked me into abandoning an early edit of the foreword so that I might be in his book with my raw social media voice rather than the gussied-up for mass consumption magazine voice. I love that The New Yorker heavily praised the artfulness of his documentation and Mother Jones said Protest City “works on different levels, with raw documentation and vivid reporting that drag you headlong into the fray. Dundon’s photos make you feel, elicit emotion, make you wince.”

Rian and I have hung out a little bit in Portland this year. I’ve spaced out over the zine-style photography collections that Dundon has produced. He’s a legit artist, and on December 13, the photo agency Magnum will host at its foundation in Manhattan a signing and discussion of his book .

When we spoke by Zoom on Tuesday, Rian Dundon, 42, had just returned from Clark College in Vancouver, Washington, where he’s set to begin teaching next year.

“I kinda like Vancouver,” he told me. “I’m gonna move over there if it works out with the job.”

How and when did you come up to Portland. Is Oakland where you were born?

No, I was born in Portland. It all comes full circle: 1980. But my folks were from the East Bay. They had me and then a year or two later they were like, let’s move back to the support zone and be around family. They did.

So where in the East Bay were you?

I didn’t even grow up in the East Bay. They were living in San Francisco in the early eighties and then my dad got a job down in Monterey, which is where I grew up. Then later, through long, circuitous routes in Oakland for I guess six or seven years. Sacramento, then Oakland.

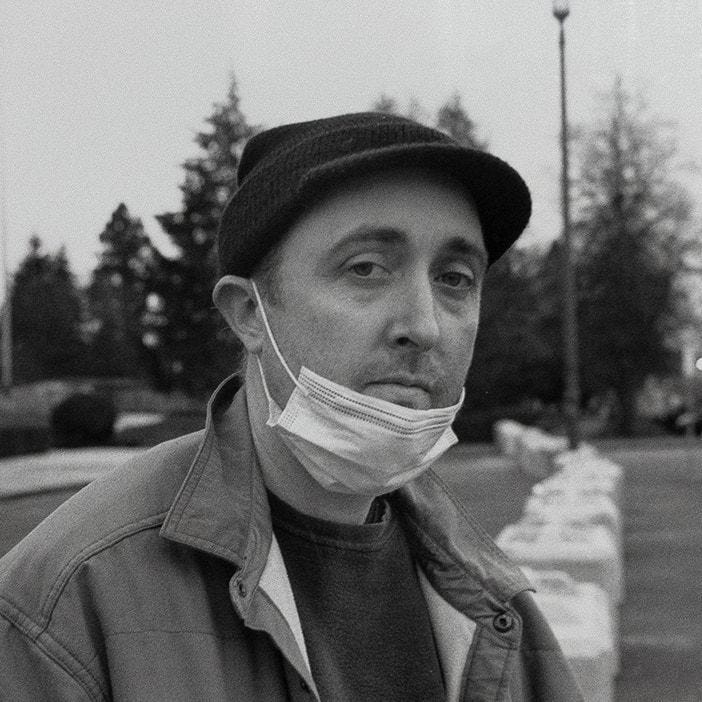

Photo by Blake Andrews. Salem, Oregon. Inauguration Day, 2021.

Where were you in Sactown?

Oak Park. Thirty-third and X.

Really.

Yeah, loved Sacramento. I moved up there. I was in Santa Cruz, going to grad school and then my wife—now ex-wife—was living in Sacramento and I ended up moving in with her. Together we moved to Oakland.

You moved to Sacramento after the gentrification happened, I’m assuming. And it’s not that bad. Of all the gentrified places in California I find Oak Park to be the most gently gentrified, you know? It feels very inclusive.

I was only there for a year. We were on the edge of Oak Park, right there on Broadway. Yeah, it didn’t feel like a heavily gentrified area, not at the time, at least. It seemed pretty sweet to me. Sacramento has always been a sleepy town. That’s the way it felt to me, too.

What’s your education background? I didn’t know you had so much education.

Highly educated, Donnell! [Laughter] Yeah, I have a master’s degree—an MA, master of arts—from UC Santa Cruz. It’s a really awesome little niche program they have called Social Documentation. It was originally in the Social Sciences division, Community Studies, and then while I was there they switched to the arts division, Film and Digital Media.

Now it’s an MFA, but it’s a pretty cool alternative to j-school, journalism school, in a sense. It’s more geared toward long-term projects. You take the whole two years to work on one project that you do intensive academic research around and then production or whatever. So most people go in there trying to be filmmakers. But it’s all media. They have photographers and writers and audio people.

So a project like Protest City has to be like the purest practical application of what you were meant to do, right? Unless you’re talking about films.

Yeah, I guess so. I’d already been photographing some of the political protests and partisan violence here in Portland, the right wing rallies and the Proud Boys and whatnot. Even before that, in Berkeley and Oakland, before the pandemic. So, I was in that headspace already, kind of visualizing those public events and I live like a mile from the Multnomah County Justice Center. When it started happening, I was just… walking down there, like any of these other rallies that I’d been photographing! It was an easy segue into something that ballooned into something much bigger.

Could you tell it was something significant immediately?

The first minute I got down there, because they had already tried to light the Justice Center on fire and broken the windows out that night and started a fire in the office there. It was like a million riot cops and everything else. I’ll have to look in the book, but I think it was the 29th of May.

People had been protesting every night for about six weeks and it was heavy, especially at the beginning. But you can’t sustain that forever. When Trump sent in the feds, that brought juice to it. Brought everybody back and then some, because this “defend Portland moment” could obviously unite a lot of people.

You’d shot Occupy stuff, right?

Not really. Protests are a perennial subject matter for any photographer, especially when you’re younger and starting out, because it’s accessible. But it wasn’t like something I was particularly interested in, in general. When Trump got in office and I started to see these almost cartoonishly partisan dynamics happening, that piqued more of an interest for me at that time. When the Giants won the World Series in 2014, I was down at those riots, too. That interesting, too.

Ninety nine point nine nine percent of people were not there in Portland. What was the ebb and flow of it? You’re shooting over how many days? How did this all pick up?

Looking back you can see where it ebbed and flowed, but in the moment it was hard to judge. I didn’t think it was going to last that long. I don’t think anybody thought it was going to last that long. And it probably wouldn’t have, except that a month, six weeks out when they sent in the federal police in the fatigues; these are the picture that people started to see. At that point, to me it looked like the protests were fizzling out before that happened. People had been protesting every night for about six weeks and it was heavy, especially at the beginning. But you can’t sustain that forever.

When Trump sent in the feds, that brought juice to it. Brought everybody back and then some, because this “defend Portland moment” could obviously unite a lot of people.

Explain what you mean.

Yeah, I talk about it like everyone was there, but initially the the law enforcement was Portland police and county sheriffs and whatnot—maybe the state police. Then in July, under the pretext of protecting monuments and federal facilities, which is the federal courthouse down there—which hadn’t actually been a target until later—Trump specifically sent federal police to bolster the law enforcement response.

Straight from the start, they’re wearing Desert Storm fatigues and they’re all geared out. Really physical with people, from the start. So, the federal courthouse is just across the street from the county courthouse. Everybody’s focus just shifted ninety degrees and it became almost all-out warfare, with these dudes in camouflage running around. As you’ve read, they were snatching people in unmarked vans, they were doing sneak attacks from the back of the park. They were popping up out of back doors and wrangling people up. It became a much bigger thing. Where there had been a few hundred at the end of June there were thousands and thousand and thousands of people and not all just activists-type people. It was that type of dynamic: Trump sent federal goons to Portland to fuck up protestors. It reinvigorated the momentum behind the protests.

I know that there’s footage online of you getting caught up with the feds. Maybe I can use it. Can you explain how and when that happened?

Click on the image above to see the above video of Rian Dundon (white pants, blue sweatshirt) being steamrolled by federal law enforcement agents that Twitter quickly sent around the world.

July 21st I was standing with a group of other photographers in front of the federal courthouse. Part of the portico, which had been boarded up with with plywood, had been lit on fire. We were just like moths to a frame, a bunch of photographers taking pictures of a fire and you can see in the video: A pack of maybe five or seven federal police come around the back door of the building, came up behind us and just… I didn’t see ’em comin, but they grabbed me and basically rag-dolled me across the sidewalk.

I’m not an activist, I’m not trying to fight cops. I’m there to do my job. When it’s like, “You gotta be on the sidewalk or you’re going to be arrested” I’m the first one on the sidewalk—where I was at this moment. So, I didn’t think I was in any danger, legally. I was just casually walking away when they tossed me.

You see in the video that another officer had also rolled out a cannister of tear gas or smoke gas of some sort. Just by chance, when I rolled on the sidewalk that cannister exploded—on my ass. It’s comical actually—there’s literally an explosion on my ass and on my low back. It hurt like a motherfucker and I got third degree burns on my back.

The worst part is after this happened, instead of letting me get up and walk away, this cop comes—and this is after he rips my press badge off—throws me down and kneels on me and puts his nightstick on my neck, in the smoke from the cannister that’s just burned me and holds me there for 10 seconds. I’m in a fetal position with my camera and all I’m saying is, “I’m press! I’m press! I’m press!” and eventually he either heard me or decided I wasn’t worth it and got up and let me walk away. I was this close to passing out and totally frazzled.

I caught my breath and ended up staying down there that night. It was a really intense night of conflict with the federal police.

How often did you go out there? How many times do you think, in total?

The book represents a year of work, end of May to the beginning of August, 2021. I don’t how many times total, but when it was really going on like that—especially when the federal forces were here—I was definitely trying to be there every night. I’d have to count it up, but the book represents at least 50 separate days.

When you were shooting over those 50 days, were you trying to make an art book, or did you just want to document this time?

I’m always trying to make an art book, Donnell. That’s what I do. [Laughter] I wasn’t like, This is gonna be a good layout, next to that other one. But project-wise I’m always thinking in a deeper sense. Pictures to me, are cumulative. It’s not disposable to me either, like journalism is. Like, I got that picture that night, now it’s on to the next one. I’m trying to accumulate layers with any project and this is no different. At the same time, this was international news, so I was sure to be there as much as possible, just to be on hand. That’s how the pictures were going to come.

I want to show you some pictures. Can you talk about the cover image? I’m sure you went through a lot of back and forth.

Yeah. That picture, it’s a horizontal. So when you open the book up it’s a wrap around to the back cover. It’s a statue of Thomas Jefferson that’s freshly toppled outside Jefferson High in North Portland. That was early in the morning. That next morning after the protest I hadn’t been present, but at 6 in the morning or whatever I drove up and it was still laying on the curb there.

These pictures are pretty blunt pictures. It’s like: boom. There’s a lot of almost forensic images in this. I’m using a flash, it’s very square. It’s in the frame, right? This is one of those and I like this picture. It wasn’t my first choice for the cover, but when you’re working with a publisher there’s some negotiation there. And I’m fine with that. They liked it, I think because of that graffiti in the back that says slave owner on the pedestal the statue had been on.

I’m going to go with them. They make more books than I do. To them there was a narrative in that—Oh, this thing’s been thrown, somebody took the time to write slave owner there, it’s very easy to say, Oh, okay. That’s a racial justice protest moment. Got it. And it’s graphic. Personally I don’t think any picture with words in the picture should rely on the words to be a good picture.

We all win and lose battles. It works fine. What kind of equipment were you using?

These are digital cameras I use. And these are small, portable Fuji-film brand cameras. I have a couple of them. They’re small, pocket, Rangefinder cameras.

Can we talk about this image?

July 16, 2020. Officers with an ICE Special Response Team assemble outside the Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building before launching an offensive against protesters. Department of Homeland Security acting secretary Chad Wolf was in Portland to survey the progress of what he called his “solemn duty to protect federal facilities and those within them."

This is a group of DHS and probably multi-agency federal officers standing outside one of the federal facilities downtown, kind of preparing or eyeing a group of protestors. who are maybe inching a little too close to their facility and getting ready to respond to that.

The effect of the flash is really powerful here. It’s this otherworldly thing that’s happening in downtown Portland. And just the flora here? It’s so Portland.

They’re camouflaged. [Laughter]

Do you remember when things changed? There was a real gravity to Portland protesting after Ferguson in 2014. I remember driving back into town with my girlfriend after a trip to California and slapping hands with all these white people in the streets as we were driving through Southeast Portland. Those felt different.

I’ve photographed a lot of protest, including the Iraq War 20 years ago when millions of people were trying to stop Bush from bombing Baghdad. But, dang, they go hard in Portland. Even my friends in Seattle are like, Ooh. We didn’t think you had it in ya!

Yeah. Seattle does not take challengers lightly.

They don’t play.

A friend of mine saw that big Indian event movie that was out last year. Oscar-nominated and it had strike underpinnings. (The film being screened was RRR.) Screened at the Hollywood Theater. And yeah, there’s a protest motif in the film. The audience got super into it and started chanting. My friend, who’s been up here forever, said to me, “God, people in Portland just love to protest!”

[Laughter]

It’s like the city has a hard-on for, is just spoiling for a protest. What is that all about, in your opinion?

That’s funny. I was just hanging out with this ex-journalist from Seattle this weekend and she was asking me that same question: What’s up with the Pacific Northwest and protesting? Portland and Seattle. I don’t know, because people here are generally reserved. I think maybe Seattle’s the same way. Portland’s kind of a rainy, sleepy place. You walk down the sidewalk, people won’t necessarily conversate. I feel like people are in their homes here, at least compared to The Bay Area, compared to Oakland, for sure.

[Laughs] And there’s passivity, right? That famous passive-aggressiveness. But given the chance to protest people go nuts. And maybe that’s why. It’s pent up a little bit, and then you get a chance. I don’t know. It goes back probably a lot deeper than that. I think some of the answers are the work Mic Crenshaw talked about, the anti-Nazi, anti-fascist kind of bedrock here. Which makes sense because the rest of Oregon and this region is pretty red.

The thing that makes it interesting is that the people in your book aren’t just engaged in earnest protest. There’s theatricality to it. And, this is just me talking, I’m not assigning this to you, but there’s a disproportionate amount of cranks in Oregon. There’s a lot of weird people who came out of the California sixties and intentional communities that are borderline cult communities. I don’t think you can divorce the form of the protests from that.

I think that’s accurate. One thing I don’t bring out that much, because you’ve got to be sensitive in how you approach it… a lot of the craziest shit that I saw happen, as far as vandalism or violence or physical stuff… I’m not generalizing, but in many instances when shit would really get popped off it, it would be sparked by something that somebody did. And that somebody, um.. there’s a lot of mental heath shit going on here in Portland.

Thank you.

There’s people out there who are like, Oh, protest? Let’s fuckin’ go. Let it out right now. I definitely saw people, visibly with issues, be the first ones in line to break a window. And once that energy goes out it can spiral.

It’s tough for people to talk about, but it’s necessary. So I’m glad you brought it up. Tell me about the big event in New York.

December 13. We’re doing a book launch at the Magnum Foundation, in Manhattan. It’s the non-profit wing of the Magnum photo agency. They do great work in documentary photography. It’s a small space, but I think they have a capacity. It’s open, and I’m going to be in conversation with Noelle Florés Theard, who’s a digital photo editor at The New Yorker. She’s the one who worked on the piece they did about the book over the summer. We’re gonna have a little convo, some slides and a book signing. Questions or whatever.

You gonna be a Magnum dude now?

I wish. I don’t think they’re taking applications. It’s interesting. I came up in photography as a voracious consumer of what those Magnum guys and girls have done. Susan Meiselas, a famous photographer, started the Magnum Foundation. As far as I know, she’s the president. What they’ve done and what they do is fund, not work that looks like traditional Magnum work at all, it’s almost the opposite. They’re really invested in underrepresented voices, people reporting on their own communities. They’re not someone flying into a war zone to take pictures, but it’s all about personal connection to stories, underrepresented voices and communities, and divergent ways of using images to tell stories. You’ll see that a lot of artists they’re supporting are doing collage work, archival work, or a combination of that with traditional reportage.

That’s really interesting.

Not to toot my horn. But me withstanding, a lot of the artists they’re supporting are some of the freshest voices in documentary photography.

That’s a very humble way to put it.

Is there a link to buy his book in here that I missed? I want to cop this right away.

This is a great one, D