Words from Kevin Powell's mouth to your mind

The Grammy-nominated wordsmith has a roundabout LA story to tell

Photo by Evangeline Lawson

Note: A fine companion for today’s print version is my Zoom call with Kevin, laughter & stammers & grammar fails & all.

Grocery Shopping with My Mother is such an evocative title that Kevin Powell’s poetry collection grabbed my attention straight away. What non-orphan doesn’t remember the intimacy of co-piloting with their mum. Your shorthand and initial bursts of usefulness. The ongoing negotiations for snacks.

These trips are especially poignant for kids like Kevin and me, who were raised by single parents.

Presently Grammy-nominated for the spoken-word version of his 2022 book, he’s among the most recognizable Black writers we have, if only because of his early work in the seminal reality show The Real World. My man is arguably the most memorable “character” from the New York season.

I never wanted to be a music journalist. I wanted to be an investigative reporter like Woodward and Bernstein for the Washington Post. When I was writing for independent publications, like the Amsterdam News, the Black weeklies, that's what was my impetus. It was Harry Allen, who was down with Public Enemy, who asked me one day, did I write about music? I lied and said, yes, and that's how I got my first gig.

But real readers know Kevin Powell’s name is on so many impactful articles and books. He’s spoken about Black life on camera and before live audiences since damn-near the first Bush Administration’s end. His Vibe mag byline was dead up in the singular moment in American pop culture named The East Coast-West Coast Beef. Dude has run for Congress, twice. An activist at heart, Powell was named International Ambassador for the Dylan Thomas Centennial, back in 2014.

He’s on The Sojourn podcast specifically because of a powerful Shopping track called “Dear Kobe,” and the February 5 Grammys ceremony at The Crypt, in downtown LA. There’s another West Coast tie-in, but we’ll save that as a surprise.

Kevin and I go back to the anthology Step into a World, which he edited with the late, great Joe Wood. I couldn’t believe I was included among so many famous young Black writers. The fact that my essay “Are Black People Cooler than White People?” opens the terrific anthology made that late-90s moment really matter for me.

Let me not belabor the relationship. Below are some questions that I asked my friend Mr. Powell, along with some answers he threw back at me.

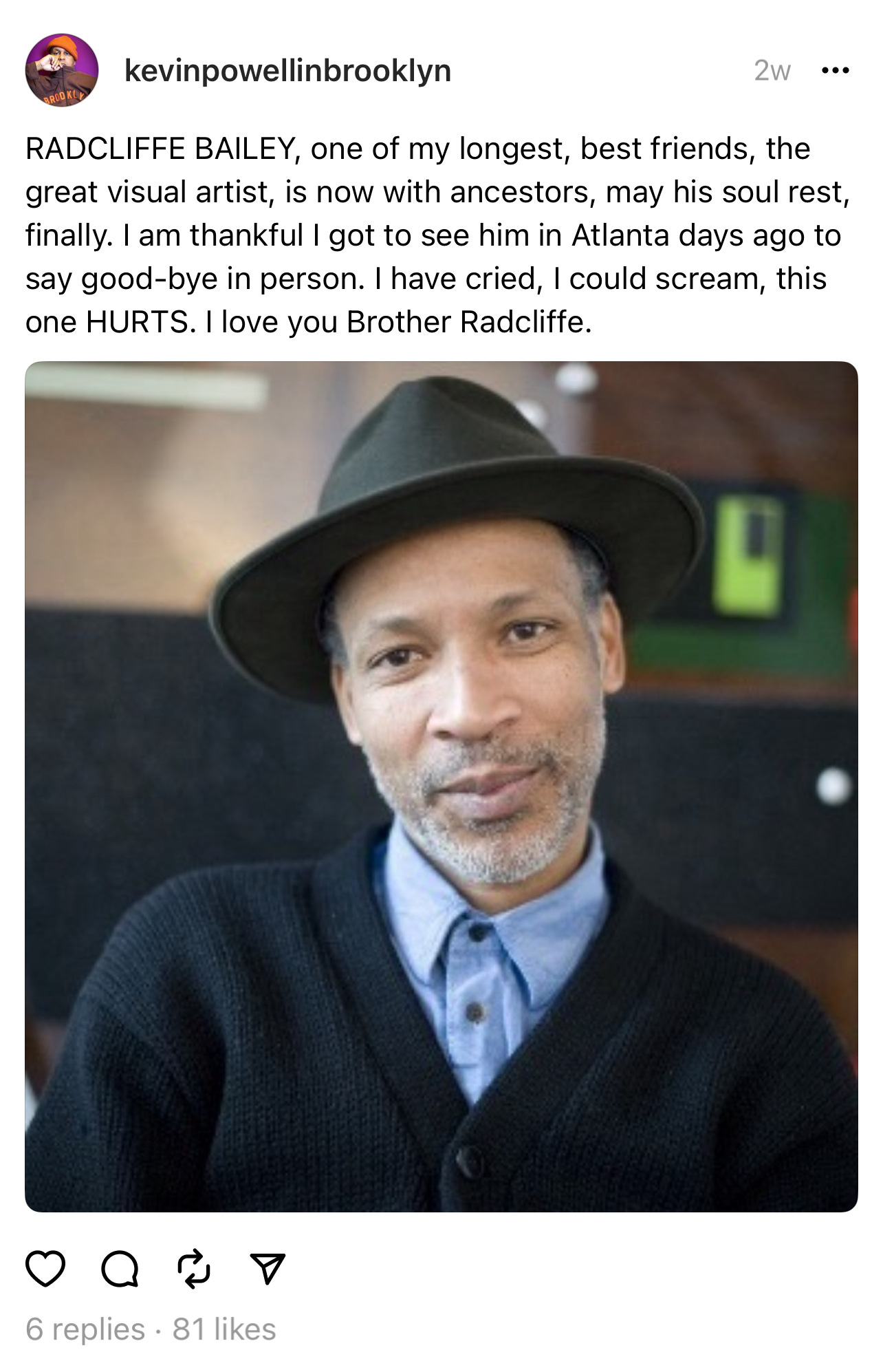

RIP Radcliffe Bailey

Let me give you the proper introduction.

I'm very happy today to have my friend and colleague—and kind of an inspiration—Kevin Powell on the West Coast Sojourn podcast. It may make people wonder why he's on the West Coast Sojourn podcast, but once we talk, you will know.

Kevin, welcome.

Man, thank you so much for having me. I mean, well, I love the West Coast. My wife is from San Diego. She went to UCLA, so we will be there living soon enough because I promised her we're gonna move out there. We're done with New York.

I was hoping to save that for later, but we will come back to that.

I'm sorry.

Having a vocal arranger made a huge difference because she challenged me in my voice. She's like, Let's stretch your voice out. Let's do different things for different tracks and let's figure out how to make this poetry into music and in a different kind of way. I mean, we got a Grammy nomination, so I guess we did something right.

I have plenty of questions, especially as we had that exchange today about spending your mornings a certain way. We'll come back to that. I want to start by going back. My very first literary reading was with you.

Wow. Yeah. Was it? What city?

It was in New York. It was Brooklyn. Now maybe we can reverse engineer where the actual event happened, but it was a Barnes and Noble in Brooklyn for Step Into a World.

Oh, my gosh.

Yes, yes, yes.

You know, it was crazy. I was just in Atlanta this weekend, um, or a few days ago, for the celebration of the life of Radcliffe Bailey, his artwork is a cover of Step Into a World.

Oh my goodness. That is amazing. That is really good. I want to talk about your work and all that, but let's talk about Bailey a little bit later. I'm working on this book that concerns West Coast hip hop. And I was listening to the Watts Prophets just as I came upon your work. I wanted to know what keeps you reaching back to spoken word as a form of expression.

That's a great question. It's funny because the Watts Prophets are some of the folks that I listened to a lot when I was working on this album. I've been a poet since I was very young.

And it's interesting that you asked that question because my first writing love as a kid was fiction. I was in love with Ernest Hemingway and Edgar Allen Poe. And I love the work, the writings of Shakespeare. I didn't know that black writers or Latinx writers, Asian writers, or indigenous writers existed. You know, I barely knew that women writers existed, but I loved fiction.

But, you know, poetry because of hip hop exploding, I almost feel like my life parallel [to] hip hop us in this Generation X. And so I started writing poems in college. They were political protest poems, of course, because it was like anti apartheid movement. You know, we had our own versions of George Floyd back then in New York with Bensonhurst and Howard Beach. Obviously, LA exploded with the Rodney King situation. So, you know, poetry was just immediate for me. Langston Hughes is my favorite writer ever. I don't know if you knew that. I absolutely love Langston Hughes, because he gave me a model—gave a lot of us a model—of how to navigate this world called being a writer. And just his poetry, it was just accessible.

But I walked away from it, because of journalism; I had to make a living. Poets don't get paid. [Laughs] You know what I'm saying, Donnell? It was a hard decision, but you know what was happening in the nineties. Quincy Jones starts Vibe magazine. I was blessed to be a writer.

I never wanted to be a music journalist. I wanted to be an investigative reporter like Woodward and Bernstein for the Washington Post. I was very clear about that. I was going to expose—

That, that I did not know about.

Yeah, when I was writing for independent publications, like the Amsterdam News, the Black weeklies and stuff like that. That's what was my impetus. It was Harry Allen, who was now a public enemy. You know, who asked me one day, did you, did I write about music? And I lied and said, yes, and that's how I got my first… my first gig was actually for San Francisco Weekly. My music editor was Danyel Smith.

I did not know that.

Yeah. And in fact, some of my first music pieces were in San Francisco Weekly, LA Weekly, Thrasher magazine because, as you can see behind me, I have five skateboards. I grew up a skateboarder. I still skateboard.

I just love music. I mean, but I also was a kid who listened to Led Zep, Pink Floyd and disco and hip hop and R& B, Motown, all of it.

I have to ask, what did you cover for Thrasher?

Cypress Hill. It was Cypress Hill. You know what I mean? Cause they had that… they had that kind of feel, man.

And I don't know if it's politically correct to say it now, but… man, “How I Can Just Kill a Man” is one of the hardest beats I've ever heard in my life. I just love the way they flowed, man.

Yeah. You know, it's also that magical thing when you put a New York DJ with a West Coast MC.

Yes. DJ Muggs. Shout out to DJ Muggs. I was never one of those East Coast cats who had a problem with the West Coast. I mean, first of all, when I heard West Coast hip hop, the Southern twangs, I'm like, my mother, I'm one generation removed—my mother is from South Carolina. She's a Geechee. That's, that's our people. You know what I mean? And so when I heard the dialects, I was like, Oh, that sounds like down South to me. And sure enough, a lot of them, as you know, had migrated from the South to the West Coast. And that's where you heard this particular kind of flow.

I just love music, man. And the energy of our music and poetry was an accessible way to do it. And, you know, it's interesting, because around ’96, ’97, I was talking to an African drummer and a DJ, and I had to make a very serious decision at the time. I was thinking about putting together a poetry band. I kid you not. I was thinking about Gil Scott Heron, the Watts Prophets, all of that. And I decided instead to just become a solo speaker and I ended up being on the speaking circuit all these years. But something felt incomplete all these years. And that's why I came back to the poetry because I was like, I gotta. I'm a poet, man.

There was a period, Donnell, when I didn't even write poetry for years. I ran for Congress twice, I was married and divorced, I'm happily married now. A lot of stuff happened. But as you know, as a writer, you gotta follow, you gotta follow your passion, man. You gotta come back to it. And poetry is one of the most important things to me in my life. It's, it's really, I can't imagine life without poetry. I'm not going to stop ever again, I can tell you that much.

Well, let's talk about the, the, maturation of your delivery. Cause I'm struck by the musicality of the whole thing. I mean, I haven't listened to everything going back to Slam or Nuyorican Poets Cafe. I just know that there was a certain point where the albums… well, I don't know, that there was necessarily as much effort put into the production of the music as what went into the rhymes. Why does your album sound so good, dude?

Thank the Beatles. Thank the Isley Brothers. Thank Lauryn Hill. Thank Kendrick Lamar. Thank the Beach Boys. Thank Pink Floyd, Led Zep. Thank Joni Mitchell. Thank Carole King. That's what I was listening to when I was working on this album.

At the beginning, I definitely listened to the Watts Prophets. I definitely listened to the great dub poetry out of Jamaica and the West Indies. Shout out to the great dub poets. I definitely listened to the Last Poets. I definitely listened to Gil Scott, Nikki Giovanni, Camille Yarbrough, people like that. Sonia Sanchez's albums. But my co-producer, a woman named Tyneshia Hill, who's an amazing singer-songwriter, vocal arranger. She said to me, Stop listening to all the poetry, because you're going to sound like the rest of everyone else and you need to do something different.

And you have to create a love of music, you know, to just do what everyone else is doing. It's not to diss anyone else, because you know I come out of a tradition. And I'm clear about that tradition—there's no me without Maya Angelou and Nikki Giovanni and Amiri Baraka and folks like that who are poets... but, man, I'm a Kendrick fan. I'm a Lauryn Hill fan. I'm a massive Beatles fan, you know, and I was like, I want to create something. Man, if I, if we had time, I would have been rock and roll on that album, bro. There'd be some metal on that album, straight up, because I just, I love music.

And so we decided we wanted to do poetry in a way that we felt hadn't really been done by a lot of people. And, you're right, it does become kind of cliche, kind of becomes the stereotype when people just snapping their fingers and people either saying it very softly or they're just screaming. Having a vocal arranger made a huge difference because she challenged me in my voice. She's like, Let's stretch your voice out. Let's do different things for different tracks and let's figure out how to make this poetry into music and in a different kind of way. I mean, we got a Grammy nomination, so I guess we did something right. But I'm glad you asked that question. It was eight months we worked on that album.

The vocal arrangements are the thing, not just where she pushed you. And you know, I listened to you and I've heard you in person and I can tell there's been a growth here. I didn't know whether this was something that happened over the years since the last time I heard you read or if it was just all about this big push because you had a coach.

Both. Absolutely. You know, it's interesting you ask that question or say that because, um, I hadn't read in years. I, you know, I don't do a lot of readings. What I have been doing is a lot of public speaking. When I first started speaking in the mid to late 1990s, I was literally doing whole speeches because it was just different. Our attention spans have gotten shorter, as people in this country, in this world, because of—I believe—technology, social media. And I found myself doing speeches over time that were less speeches, but more interactive conversations with the audience. So that definitely found its way into this poetry album as well.

No one has asked me that, but that definitely is a part of it. And her pushing the heck out of me, like, Kev, I know you can do this better than that. I mean, writers need editors. I will never think I'm above an editor. Everything that I write, someone else reads it. I will never think I'm above an editor. So why can't I have a vocal coach, like a singer does? Some of the rappers absolutely need some vocal coaches, so why can't the poets have vocal coaches too?

We we've gotten so far in the music thing, because I was curious about it. But we haven't even established what this project is about.

This started as a bunch of social media posts—

Your mortal enemy, social media.

Yeah.

But you were, you were, you were, you were writing about your mother. Tell, tell everybody about that.

About five years ago, my mom got sick, really sick to the point where she couldn't even go to the grocery store. And I'm an only child. I didn't know my father. You and I have shared our personal stories and we've had a lot in common. I saw my father three times until I was eight years old, off and on. They were never married. And then he was gone. And I found out just 10 years ago that he had been dead since like 2001.

Wow.

And so my mom is my father, you know, and, and it's a complicated relationship because my mother is very old school, very, um… set in her ways, and so it's definitely been a tough love. You know, when you and I talked this morning? Brother, my mother was my alarm clock when I was getting up. So I still stay, waking up at four or five o'clock, naturally, because I could hear my mother's voice: Get up! And that was the kind of way that she would say it. You know what I'm saying.

Mm-Hmm

But she got sick and she ended up in a hospital. She said to me it's the first time she was in a hospital since she gave birth to me, and I was terrified that I was going to lose my mother, man.

I asked my mother, what does she need? She said, well, I need help going to the grocery store. And it just began simply as me taking her to the grocery store every week in Jersey City. I've been in Brooklyn for 30 years, and I've lived here far longer than I lived in my hometown, Jersey City. But I just started going over there and helping her with things and I just would post. I just started posting and it wasn't even so much. It was like my therapy, like, man, I just went grocery shopping.

I took my mother to my holistic doctor. I'm a vegan, and, you know, sometimes vegans can be way over the top with this. Don't eat this. Don't eat that. Man. I took my mother to my holistic doctor and she listened to him and he wasn't telling her not to eat meat or fish or anything like that. But he was just saying, here's how you can reverse the diabetes. Here's how you can, you know, reverse the arthritis. Here's how you can reverse the high blood pressure. She said, okay, cool. Then when she got outside, outside on the streets of Brooklyn, she said to me, I don't give a F what that MF says. F him. That N I G G A don't know anything about me. I'm going to eat what the F’n want. [Laughter] That's my mother in a nutshell.

I would post that and the responses to people's social media were hilarious because they're like, that's my mom. That's my dad. Or, you know, my mother's gone. I wish, I wish she was cursing me out right now. It was just funny, the reactions. And at some point I said, man, Grocery Shopping with My Mother—that could be the title of my poetry book. ’Cause I was now writing poetry again. And so I just began. The need to accumulate stuff and the cover of the book is my mother and I in a grocery store.

My wife— we weren't married at the time—is the photographer who shot the cover. She snuck it with her Android phone and it became this book. The book came out and it was, in my mind, Donnell, for a minute: Man, I really would like to turn some of these 36 poems into an album. I've always wanted to do an album.

I don't want to sound morbid here, D, for a second. But listen, brother, we've lost so many people. Shock G, you know, Coolio. The list is endless. You know, DMX, who are only in their 40s and 50s. Black males over the last couple of years. And COVID hit. Kobe's gone. I have a piece about Kobe, as you know, and I just, I just said, man, I don't know how long I got. I'd love to live to my nineties, like Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, but just in case, let me go do this album right now. And I want to call it Grocery Shopping with My Mother. And the reason why I picked nine tracks is because Marvin Gaye's What's Going On? has nine tracks. Prince’s Purple Rain has nine tracks.

Carol King's Tapestry has nine tracks. And Michael Jackson's Thriller has nine tracks. I'm like nine must be the lucky number. I'm going to have nine tracks. [Laughter] That's because I'm a music head. So I, I look, I'm one of those music nerds that reads the credits, looks at how many songs are there, who produced it, who's the engineer. I've always been that cat. So it was really interesting being on the other side. But that's how it came about.

I just explained to my mother the other day what a Grammy is and that I got a Grammy nomination. You know what she said, Donnell?

No.

Does that mean you won't get money from this?

Of course.

She's about the cash. She's like, where's the money at with all of this? I was like, well, I don't know if that's going to happen, but I might win a Grammy. So, we'll see.

That's a kind of money. Hey. I want to talk about “Dear Kobe.” I talked to Kobe one time.

Oh, wow. Yeah. I wish I could have met him, man.

I interviewed him in the locker room at The Forum when he was like in year three and I just started at ESPN. Yes. And he wasn't famous enough to make it into the piece, which is kind of funny in retrospect, you know, it was a Jordan appreciation. And he had very insightful things to say, but it's like, eh, this guy, we're not really sure what he's going to be.

Do you have the audio of it? Did you audio tape it?

I, you know, maybe I did. I don't know. I've got my old tape somewhere.

I hope you have that. That's incredible. If you have that, wow.

It was a funny day and I've told the story to people, but, it was one of the craziest sequences I've ever seen in the NBA court, and you might remember the play just from the description. It was a Sunday afternoon game, Lakers-Knicks at the Forum, Shaq dunks on Chris Dudley and basically does a chin up onto the rim and thrusts his crotch into Dudley’s face.

I remember that!

Well, Dudley was furious. I’m courtside, right beneath the basket. You can see me in the clips because Dudley loses his mind out of embarrassment and throws the ball at Shaq.

Wow.

He threw it and hit Shaq in the booty.

Wow. That's right.

Kobe is staring at me. We were right in each other's sightline. You can see me going [OMG] because you can't believe it. This is happening. And my regret ever since Kobe died is I didn't go in the locker room afterwards. Man, wasn't that some crazy shit that we just saw?

New York people are funny. They always say sooner or later, I'm going to not only just cheat on New York, but I'm actually going to go marry California. And I'm like, you know what? You're right. I am definitely going to marry California. I already married a Californian and I'm going to marry California.

You just think these people are going to be here forever. Let me just say though, because when he died, it hit hard. I come out of a yoga class directly out and my kids are blowing up my phone. And I staggered. I was walking down Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood and staggered on the street. I want to know what you think it is about Kobe that made him touch people so well, that made people write poems about this particular athlete.

I never wrote a poem about Michael Jordan. It's profound, because when he first came out, I loved Kobe, you know, because he was young. He was dynamic. He was hip hop. He had made a hip hop album. He dated Brandy or went to the prom with Brandy or something like that.

And then I went through a period where I was mad at Kobe because I felt like, man, there's no way the Lakers should have lost to the Pistons. You know what I'm sayin’? Remember that super team they had put together with Karl Malone and Gary Payton and everybody?

Yeah.

But I was like, Kobe and Shaq can't get along. This is messed up. And then I started siding with Phil Jackson because Phil was like basically implying that Kobe was the cancer of the team, all of that. But I came around, I was dating someone from LA at the time who was a massive Lakers fan. So we went to some Lakers games and when they won those second two, those two championships without Shaq. I saw Kobe's maturation. I was like, you know, Kobe's a different person, you know?

And I was listening to what he was saying now, but he was a philosopher. You know what's really deep to me, Donnell, is like how people are posting on social media now, Kobe's interviews, all these philosophical things he's saying? It reminds me how I've always paid attention to how people post Bruce Lee's comments and statements, his philosophies. It's the same thing.

Sunday, January 26th, 2020. I was home and I was in deep denial that Kobe had died and Gianna and the other seven folks, God bless all their souls. I have a friend who actually works for TMZ and you know, TMZ knows everything. I said to her, please tell me it's not true. She kept saying, Kevin it’s not true. I was numb, man. You know, because we grew up with Kobe in a certain kind of way. You know what I mean? It's like, I felt that loss as much as I felt Tupac and Biggie.

And then, and I began to understand how people felt, like my mother was devastated when Marvin Gaye died, you know? And I remember when people were devastated when John Lennon got shot. But that was like, we were kids. And so it didn't hit me. I was like, why are they reacting like this? But Kobe?

I wrote an essay first. Uh, for Vibe. I went back to Vibe. I said, you know, please. And then I was in LA and I went to the Staples Center. I was at the memorial and I came inside. I had a press pass for it, but I was outside for, for a long time. Donnell. Oh man, just looking at the people, white people, Black people, Latinx people, Asian people, indigenous people, straight folks, queer folks, non-gender conforming, differently-abled folks, you know, older, younger, all generations. And I said, man, this is a phenomenon and I've only seen this a couple of times in my life: When Prince died and Michael Jackson died. I saw the diversity of people responding. You know what I mean? It's very rare that you have someone who is loved by so many different types of people and has had such an impact on so many different types of people. I think because you could see his evolution.

The sports writer Dave Zirin reminded me that when that whole thing happened in Colorado, Kobe actually apologized. He showed me the link of it. He showed me the piece that he wrote about it and people kind of skirted over that, but you could see how he had gone from all of that stuff that he was when he was younger to this Girl Dad. It was just, his journey was incredible. And then he won the Oscar. He had his whole career ahead of him. And then he's gone, he was barely in his forties.

And I never saw so many black males, Donnell, affected by something like this, except for Pac back in the nineties. We've lost a lot of people, you know, I mean, rest in peace, Nipsey Hussle. That affected me. Other folks have affected me, but, you've written about sports, you've written about popular culture. Sports is a metaphor for life. I wrote the poem after the Staples Center memorial. I just was trying to capture what I saw in LA, you know what I mean? All the murals that were going up and everything. And then when we decided to do it, make it a song, that's when I said, okay, I want to hark back to the Watts Prophets. I want to hark back to The Last Poets. I want to spit it like that, like the urgency of it. And I want the poem to feel like this kind of, you know, spiritual ceremony for Kobe.

We actually have some folks that are working on an animated version. I want to pay homage to him. We want to do Dear Kobe as a short animated piece. You're the first one to hear this brother. You can tell by how I'm holding my head and I can't even look at you that this still bothers me, that he's gone.

You know, you saw all those people, a Los Angeles that you don't always see on TV. But you know the expression, the term I should say, Kobe Stan?

Yeah.

They call this country Kobestan, because it's full of Kobe Stans. And I think what you're talking about is, his journey, is really a lot of it. The investment, especially young people, that they had in it from hero to villain. But I also think there's that charisma, you know, and I don't want to belabor the Kobe stuff and I love Kobe.

I can talk about him the whole show.

But you know, you know how when you take those jumpers and you go, “Kobe!” Kobe, you don't do, you didn't do that with everyone. You didn't go “Dr. J!” you didn't go, you didn't go “Iverson!” You went to “Kobe!” Kobe. And that embodiment that you had in him in that moment made you feel really powerful.

You know, it's really deep what you're saying, and I know we have other stuff to talk about, but I think the difference for me between Kobe and Michael is that at a certain point, Michael just seemed untouchable. You know what I mean? And superhuman, but Kobe was very human.

Even when he tore his Achilles, he came back, you know. He struggled at the end of his career, but then his last game, he gets like 60 points. It's just like, you know, they said he couldn't win a championship without Shaq. He won two without Shaq.

There was something about Kobe's humanness that I think spoke to a wide range of people and that Mamba Mentality. And, and, you know, cause I don't know what Michael Jordan's mentality was— other than now, watching The Last Dance, people think that he was an a-hole. Yeah. I just think Kobe was very human. We saw his imperfections. We saw his mistakes. We saw him apologize and try to do better. That's all of us, man. We all fall down. We all get injured. You know, that's the difference, man.

So tell me about your adventures in LA. I have to tell you my thing about LA. What got me up at five in the morning is I had to get to those editors in New York to get their attention and remind them I was alive out here. [Laughter] I started waking up early. But, because you are identified with New York in so many ways, why would you make that move?

Well, so much of my life is California influence. I'm a vegan and I've learned a lot about veganism. I mean, y'all have the best vegan restaurants in the country in the state of California, you know, a shout out to so many out there, man. Um, uh, the first time I ever went hiking in my life was in California and LA. And my New York self went out there with Timberland boots like a fool.

Do you know where you were hiking?

Probably Runyon Canyon. Is it Runyon Canyon? But then I started going to Temescal, Temescal, man, which I love, out going towards Malibu. I've hiked in a lot of places, but I mean, brother, we don't hike in New York. We hike subway steps and that's about it. And we step over rats. [Laughs]

Sometimes the elevator goes out. That happens.

You know how New Yorkers are, man. My wife's from California. She's a native. I mean, she is so California, but I've actually dated a few women who are Californians and just there's something about the energy of California that I love.

As a child, I was fascinated by y'all because I, I was, I religiously watched Three's Company, which was set in California as a kid. I would watch those game shows, man, and they would say, Live from Burbank or somewhere. I was like, where's Burbank at? You know what I mean? Remember watching The Superstar on TV when we were kids.

Yeah. That was at Pepperdine.

That was at Pepperdine University in Malibu. So I was intrigued by all the cool stuff in California, like the Rose Bowl and everything. And man, I didn't even get on a plane until I was 24. And the first time I came to California was in ‘92, the same year that I was on MTV's The Real World. And literally while we were filming, it was April, 1992—the LA rebellion happened. We literally are watching it in our loft, being filmed, watching it as the city is exploding. And one of the directors, man, I'll never forget him. Rest in peace, Rob Fox. He, you know, he was very, very socially conscious. And he said to me, how do you feel about this? I said, “Rob, I'm a Black man in America.” This is a white brother. He said, “Well, I want to do something.” And we ended up doing a documentary about young people of different backgrounds in LA in post-rebellion LA. That was my entry point to Los Angeles later that year in ’92. And it blew my mind. By that point, I was a massive, I was a big fan of Ice T. In fact, I spent a couple of days with Ice T in’91, ’92. I got those audio tapes, never did the edit, never got to write the piece, but I spent several days with him around the whole “Cop Killer” thing. Obviously I watched movies like Colors. John Singleton was my man to the end of his life. Boyz n tha Hood blew my mind, you know, and obviously NWA. I was paying attention because with hip hop, like jazz, you got the West Coast jazz history. You got, you know, Mingus and Eric Dolphy from LA. You got, you know, folks like Miles from St. Louis, East St. Louis. And so hip hop was the same way. And what it was doing for me was educating me about California.

Long before I ever got out there, I was learning the language and things like that. And people need to understand that it helped me to understand what I was walking into. So when I got to The Jungle, I already knew what The Jungle was. And I was like, Oh, these brothers got AK 47s, you know what I'm sayin’? And I'm like, but there's palm trees. It was so different than the East Coast. My wife—she now lives, we live in New York—he's like, Yo, y'all just got these gray buildings and it's just not really bright and everything, and we believe in colors in California.

That's true. You know what I mean? And so I fell in love with all of that. I've been coming to California religiously for 30 years and New York people are funny. They always say sooner or later, I'm going to not only just cheat on New York, but I'm actually going to go marry California. And I'm like, you know what? You're right. I am definitely going to marry California. I already married a Californian and I'm going to marry California.

So what's your LA look like? What's your sweet spot in the city?

Back in December, I had an event at Post and Beam in South LA. I love South LA. I love Leimert Park. You know, I, you know, I know all the great poets who have come out of The World Stage. I love that whole area. I love that area, but I also love the beaches, man. I love just kicking it in Playa del Rey and Santa Monica and Venice.

I mean, Venice and Santa Monica just remind me of The Village in New York City, because you don't know what you're going to see. And because of Singleton being from Baldwin Hills, I've spent a lot of time in Baldwin Hills. I just go all over, man. I have stayed in every part. I've been in the Valley. I've stayed in Santa Monica, Marina del Rey. You know, I've stayed West Hollywood, LA. I've stayed at Hollywood and Vine. I've kind of done the tour, man.

It's interesting you asked this question because I'd never watched Insecure when it was on. I don't know why I didn't watch it, but Issa Rae is brilliant. And so my wife and I have been watching, and I didn't realize that Insecure is an amazing journey into Hollywood. Los Angeles.

Yeah, lovingly, lovingly shot.

Oh my God, man. And so that's got me even more open. In fact, I have a, my doc, I have a documentary film on black manhood coming out in the next year, my first film as a director. And we shot a couple things in Leimert Park and also in Compton, man, you know, right in the heart of the community. There's just something about the history of California in general. When I was a kid, I didn't realize, um, Steinbeck— California. You know, I mean, I was reading these stories about California, William, William Saroyan. I read in high school, California.

Fresno. That's where I am right now.

Wow. You see what I'm saying? And I didn't realize what I was reading. And then when I started studying Langston Hughes, he spent time in Monterey. He spent time in Carmel? It's funny how the seeds are being planted. You don't even realize it, but what California represents to me is incredible natural beauty, incredible possibilities, definitely hardships because, you know, it's hard. I mean, I think about The Grapes of Wrath, how they were moving and moving and moving, you know? It's, it's so many different things.

You know, you know what signifies California to me? At the Democratic National Convention 2016—because I've covered several conventions, both Republican and Democrat—as a journalist through the years since 2000. In 2016, all these folks were trying to rally around Hillary Clinton. It was the state of California who said hell no, we’re with Bernie or nothing's happening. And I was like, That's the state I need to live in.

You need to come out here and see the complexities. When you see how the left fucks things up here you'll be a real Californian. I've got to tell you, When you come out here, what you need to do, we'll get together. I’ll take you up—

I'll be there all of February. I'll be there all of February. Fresno.

Yeah, but I'm saying is when you get out here, I'll take you up to Oregon. Black people in nature, like you've never seen before.

I love it, I love it.

I’ll send you a link to an old YouTube clip show called Niggas in Boats. It's just a Black fishing show. But that's how they get down up there. Before I let you go, the Grammys are the next big thing. You're making a film. Anything else people need to know about?

I'm really proud of the Kevin Powell Reader, my collected writings, 30 plus years of collected writings. That's out now. Shout out to Akashic Books. They put that out for me and it's a blessing. I mean, literally my first piece at age 17 is in there up until the last piece in the book, a piece I wrote about Kendrick Lamar when his most recent album came out. It's something I never thought I'd do, I hope you do it. I think every writer should do it. I think we all need to do it who've been doing this for a while. Just gather our work. And it was, it was very interesting experience to do it, man, because a lot of stuff wasn't digitized. We had to dig. I thought I could put it together in a month. That took about a year as well to gather stuff and find stuff and figure out.

And then you also have to admit, and I'm sure you've struggled with this, like, hey, Kevin Powell, everything you've written is not good. In fact, some of the stuff you've written really sucks, bro.

I couldn't face it. You’re a brave man, looking back at all your stuff. Ugh. I don’t want to see a lot of mine.

Yeah, but you know, but Donnell, you're an amazing writer and I know I said it off camera. I just need to say this, you know, you have always been one of my favorite writers. I think you're one of the most important writers we've had in this last 25, 30 years in this country, because we got to acknowledge people and I've never been one of those… you know how a lot of writers, they're insecure, they're in competition with each other. I'm like, man. No, tell people that they are dope while they're here not at some celebration when they're gone. That's ridiculous to me.

And I want to tell you when I moved to New York. Not everybody was as cool with me to me as you were and I very much appreciate it. That made the transition a little bit easier. And yeah, Step Into a World was a great opportunity. I just love that you keep growing and that you hustle and that you set an example for people.

Well, Thank you. And learn from Langston Hughes, you know, I have multiple lanes, but it all comes back to writing, as you know. Like the, all the different things you've done, the cannabis community, all of it—the thread has always been: You are a brilliant communicator and, and we have to keep that as our foundation.

We can do other stuff. We just figure out how to bring it back to the word. You know what I'm sayin’?